From factory to Florence: the English East India Company's servants and their Italian retirement

A cemetery in the Italian city of Florence may seem an unlikely place to look for clues as to the lives of Europeans in Asian factories. The so-called English Cemetery is a small burial ground established in 1827 by the Swiss Evangelical Reformed Church. The graves were situated just outside the city walls but now they sit in the middle of a roundabout on Florence's busy ring road. Built with funds raised by the British and American communities in Florence, it is the burial place of notable writers and artists such as Elizabeth Barrett Browning, Walter Savage Landor and several members of the Trollope family. It is also the resting place of a number of officers and servants of the English East India Company who, after long careers in South Asia, preferred the climate (and perhaps the bohemian lifestyle) of southern Europe to the cold British weather and society of the nineteenth century.

The cemetery is the resting place of Sir William Henry Sewell (c. 1786-1862), a natural son of King William IV, who between 1828 and 1854 served in India as Deputy Master General, then in Bangalore and at Madras, and finally as Commander-in-Chief of the Madras Army. Sir Thomas Sevestre, who died in Florence in 1842, also had strong ties with India where he had been a surgeon in the English Company, while Mary Kyd de Dornberg, who died in 1872, was related to Colonel Robert Kyd, the founder of the Botanical Gardens in Calcutta.

We know little of how these, and other ‘Anglo-Indo-Florentines’, spent their time in India. An exception is Christopher Webb Smith (1793-1871): trained at the college of the East India Company at Haileybury, he entered service in India in 1811 working as a magistrate at Etawah, Benares, Shahabad, Bankipore, Arrah, and Patna. He was related to Charles D’Oyly (1781-1845), a senior servant in the Company and English baronet with whom he shared a passion for natural history and drawing. They co-published works on the birds of Hindustan and on ‘oriental’ ornithology.

In Bihar, Webb and D’Orly were therefore not just engaged in EEIC’s business but spent a great deal of their time on cultural activities, most especially supporting the work of fellow European artists. Their collective work is referred to by art historians as the ‘Bihar School of Athens’, produced by a body of British amateur artists interested in promoting art in the subcontinent. The ‘Athenians’ had the professional painter George Chinnery as patron, and Charles D’Oyly as president. D’Oyly was born in India and was the son of Sir John-Hadley D’Oyly, the East India Company's resident at the Court of Nawab Babar Ali of Murshidabad. Charles joined the Bengal Civil Service in 1797 and inherited his father’s knighthood in 1818. Before retiring to Florence in 1838, he was a member of the Civil Service of British India, first in Calcutta where he was the City Collector of Customs, and then in Dacca and Patna. In the 1820s, D'Oyly held the important positions of Opium Agent of Bihar and Commercial Resident of Patna.

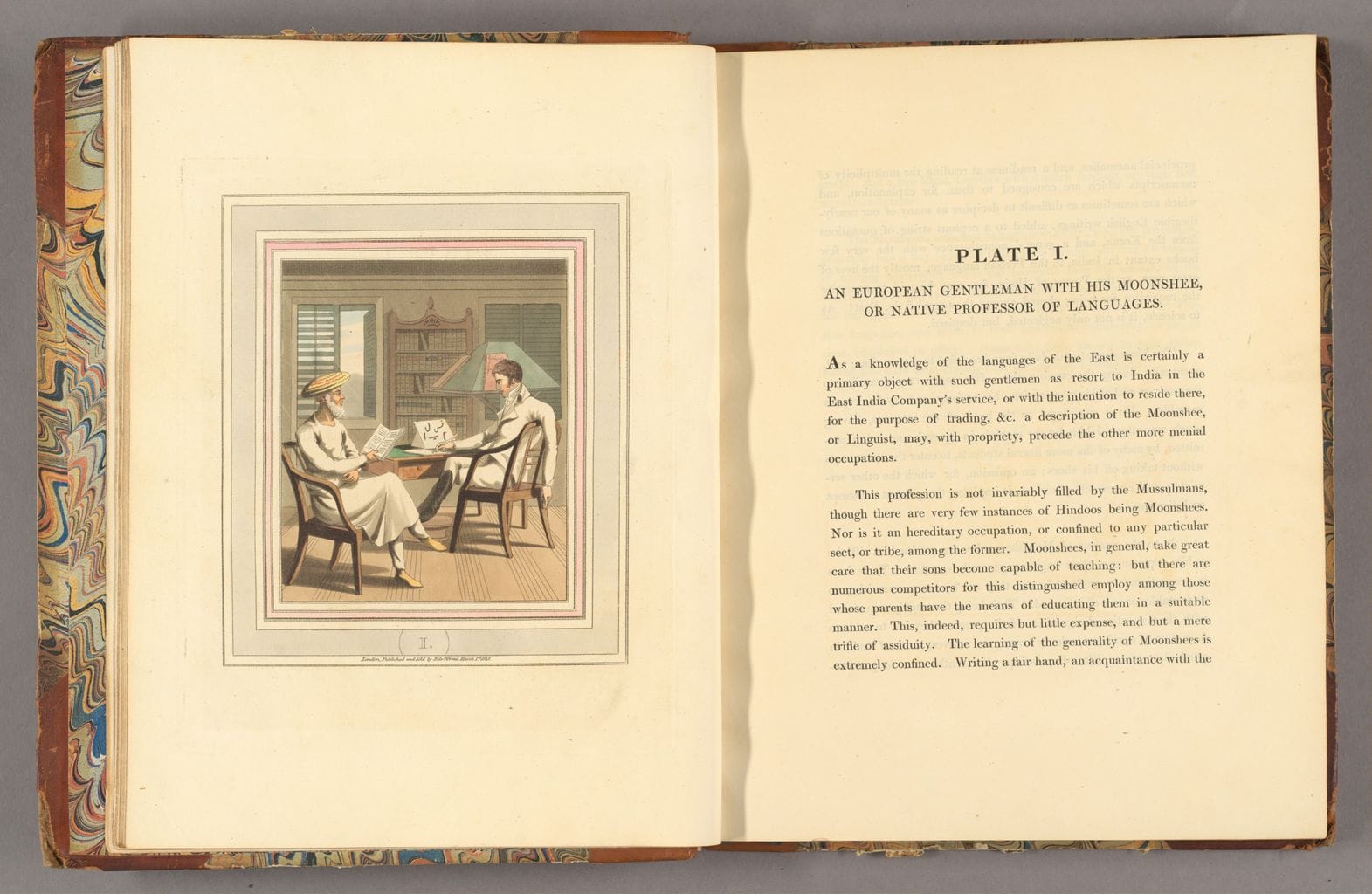

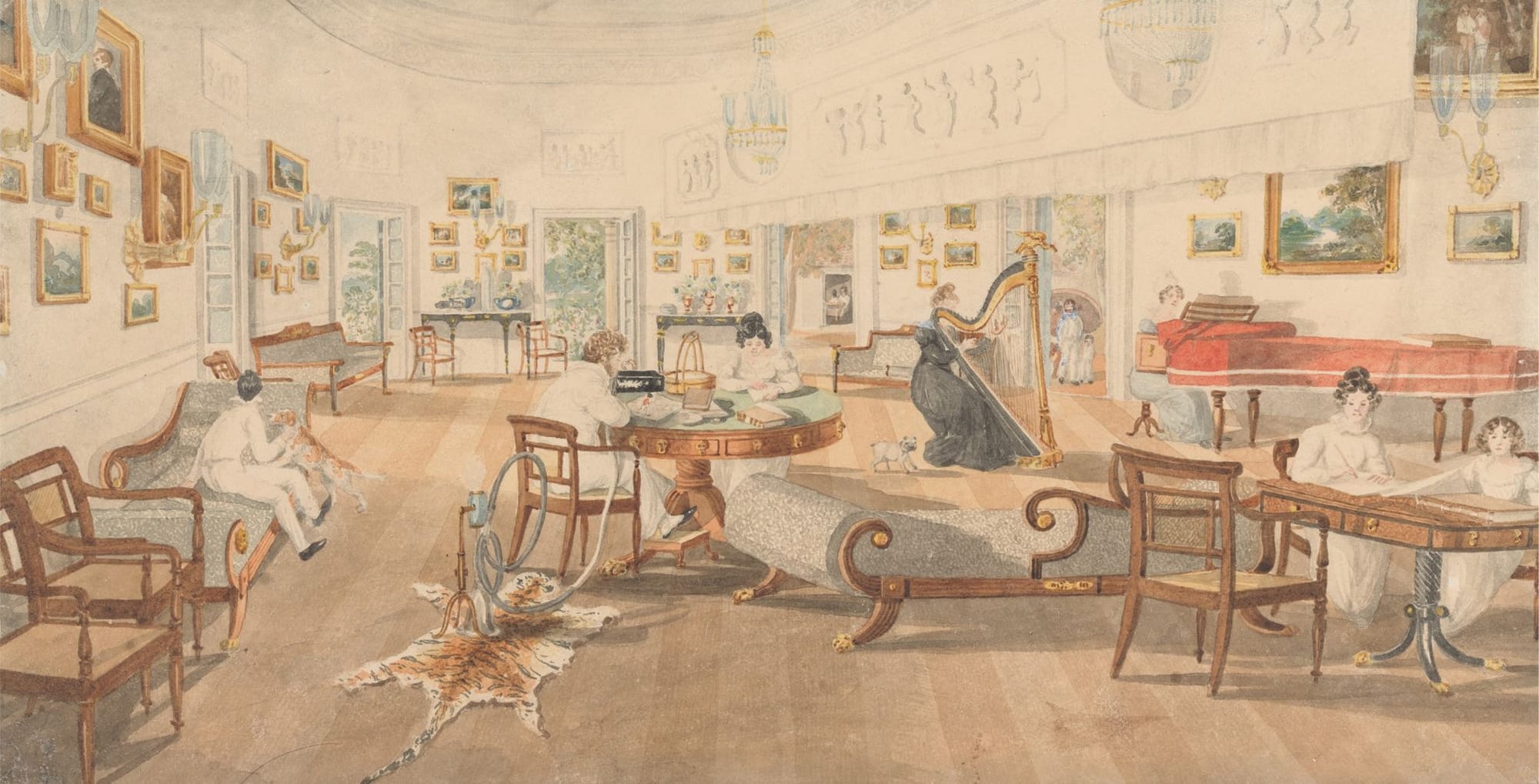

We owe to him several views of Patna in the 1820s: these are views of the cities and picturesque characters such as jugglers, punca bearers, fakeers, and snake catchers, ‘the muddle so typical of the Indian village and small country town’ in the words of art historian Mildred Archer (1967: 874). D’Oyly was most famous for his series of twenty aquatints published as The European in India, which were meant to introduce its readers to a satire of the life of a Company agent in India. These and other beautiful sketches of the domestic life of D’Oyly and other British civil and company servants testify to an interest that is ethnographic in character but devoid of any concern for Indian economic life. In a period of transition from Company to Empire, D’Oyly, Webb Smith, and others contrasted the civilizing action of British rule (expressed in a series of public buildings and infrastructures) with agrestic scenes of Indian life.

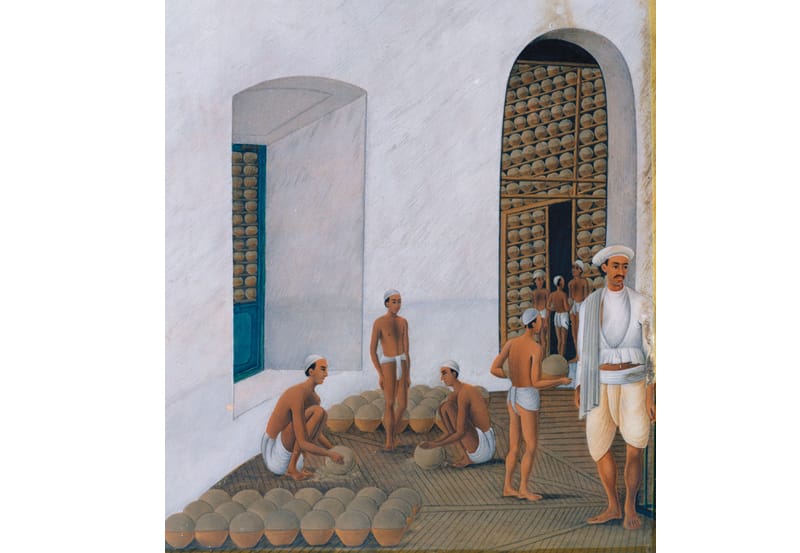

D’Oyly, who also retired in Florence and died in Leghorn where he is buried, later produced a series of scenes of Italy and its monuments (many of these are housed at the Yale Center for British Art). Perhaps more concerning for this project, is the lack of engagement with the economic life of India, most especially considering D’Oyly’s position of Opium Agent of Bihar and Commercial Resident of Patna. Here perhaps one must make a comparison with the 19 paintings on mica (a silicate material) on the stages of opium manufacture by the Indian artist Shiva Lal (1817-87). Also based in Patna, roughly a generation after D’Oyly, Lal produced a series of scenes of everyday life. These were commissioned by servants of the East India Company. Still, Lal’s artistic repertoire was not merely an emulation of British aesthetics: he was an Indian artist of the so called ‘Company school’ whose ‘intimate’ style was quite different from British artists. In fact, more than any other European amateur or professional artist, with Lal we get a sense of the world of labour and the production of opium, a key commodity in the transition towards British imperial rule, that was instead all but elided in European art.

Webb Smith, D’Oyly and others left the shores of India for Florence where they found more picturesque scenes to paint and sketch. Florence became a retirement destination for many EEIC’s servants who could not afford (socially and economically) to live in Britain. In Florence they found a community of ‘expats’ more interested in appreciating the romantic landscape of Italy than in engaging with the sorrowful state of Colonial India.

Bibliography

Mildred Archer, ‘British Painters of the Indian Scene’, Journal of the Royal Society of Arts, vol. 115, no. 5135 (1967), 863–79. JSTOR, http://www.jstor.org/stable/41371691

Bihar School of Athens: https://scroll.in/article/1059897/charles-doyly-the-british-opium-agent-who-brought-together-indian-and-european-artists

British Associations of Cemeteries in South Asia: https://www.bacsa.org.uk/florence-and-india/ [last accessed 21 April 2025]

Hope Marie Childers, ‘Spectacles of Labor: Artists and Workers in the Patna Opium Factory in the 1850s’, Nineteenth-Century Contexts, 39, no. 3 (2017), 167-191: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/08905495.2017.1311987

Charles D’Oyly, MAP Academy: https://mapacademy.io/article/charles-doyly/

India and Florence’s English Cemetery: https://www.florin.ms/India.html [last accessed 21 April 2025]

Diana and Tony Webb, The Anglo-Florentines: The British in Tuscany, 1814-1860 (London: Bloomsbury, 2020).

Tom Young, Unmaking the East India Company: British Art and Political Reform in Colonial India, c. 1813-1858 (New Haven and London: Yale University Press, 2023).