Life and Death in the Dutch Fort at Sadras

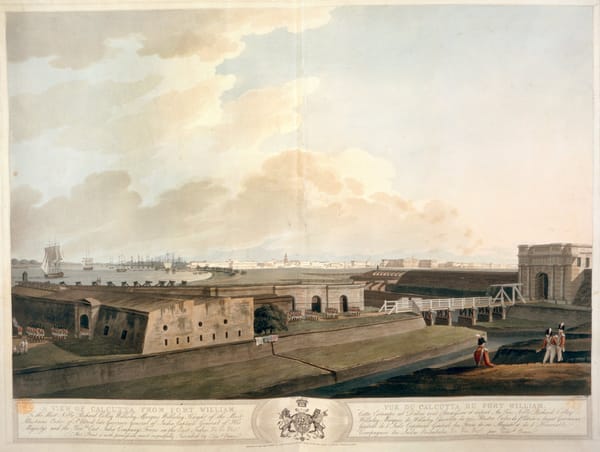

Today Sadras is a sleepy coastal village in Tamil Nadu, 40 miles south of Chennai. Tourists heading 10 miles north to visit the ancient temples of Mamallapuram might easily miss it. Just over a mile away is Kalpakkam, the site of the Madras Atomic Power Station. Between modern and ancient India, Sadras and its fort bear testimony to the role that this coast had in global trade, most especially in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries.

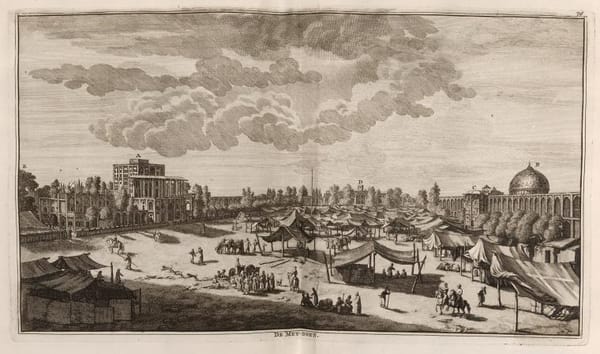

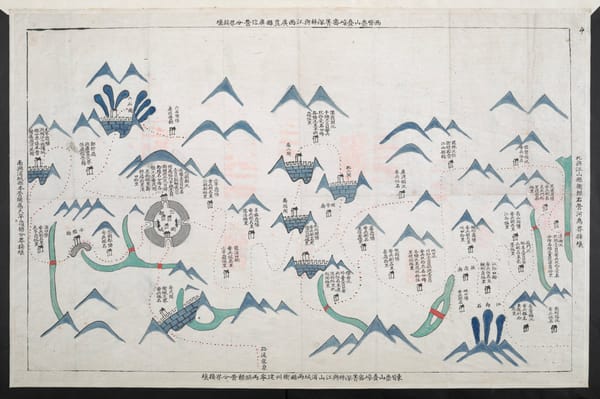

Chennapattanam (Sadraspatnam or Sadras as it came to be known), was already a flourishing region of textile weaving and a port with international connections in the tenth to the sixteenth centuries. The area was well-known across the Indian Ocean for the production of fine textiles and for its trade in spices. This was one of the reasons that attracted European traders, first the Portuguese, and from the early seventeenth century, the Dutch East India Company (VOC). Dates for the Dutch presence in Sadras vary: the VOC signed an agreement with the ruler of the Carnatic in 1612 and over the next couple of decades established a permanent presence. A fort was built, named Fort Sadras, whose ruins today are still standing. By the early years of the eighteenth century the Dutch had not just secured firm control of the fort from which they conducted trade but also leased the nearby villages from the the Moghul Diwan of South Coromandel.

Sadras – unlike its homophone Madras – did not evolve to become a metropolis, not even a city. The ruins of Fort Sadras are imposing but are also the only reminder of its past: in 1754 Sadras was deemed a sufficiently strategic place where to hold an aborted peace conference between the French and the British. Yet, most of its buildings were destroyed after its capture by the British in 1781 with further damage inflicted in 1795, 1818 and 1825 when the fort changed hands.

Written sources are not of much help in charting the history of Sadras: most of its archives has been lost, making its history much less known than that of nearby Pondicherry or Madras. More useful in reconstructing the history of Sadras are archeological sources, first among which the very remains of its fort. Set at just 100 yards from the beach, the fort has a rectangular shape with an eastern wall facing the sea (with a bastion and ramparts for defense) and a western wall with an entrance with mounted cannons and a watch tower. The surviving buildings internal to the fort show its commercial purpose: they include warehouses and storerooms, stables and living quarters for the VOC employees, their families and servants.

The built environment of Sadras – visited in July 2023 by members of the CAPASIA team – provides a unique insight into the life and death of a factory. It is also a reminder that what we see today is the result of a layering of time, of profound changes and extensive damage caused by war and time, and the more recent restoration started in the 1990s.

In 2003 the Archaeological Survey of India completed a detailed study of Fort Sadras and reconstructed some of its buildings. The compound includes a well, a kitchen, rooms with arched windows and floors made of square, rectangular and hexagonal bricks. The fort also had an underground drainage system. During the archeological digs, hundreds of fragments of artefacts were found. Earthenware and porcelain are often well preserved even in the most extreme environmental conditions. Archaeological findings show that the inhabitants of Sadras used beautiful delftware decorated with Dutchmen wearing hats, tents pitched in Holland, and coats of arms. Porcelain from China and pottery from England and Germany were also found, as well as Dutch clay pipes and glass jars with residues of white arrack.

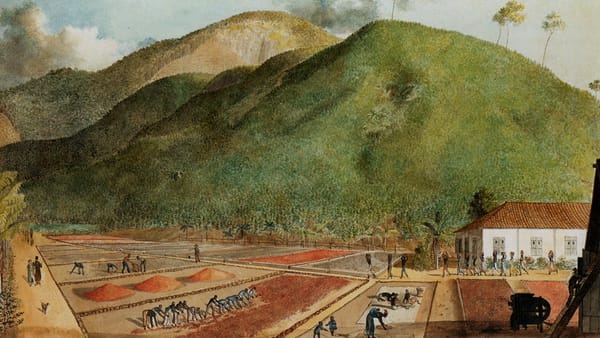

A piece of archeological evidence tells us about the economic activities within and around Fort Sadras. It is a circular structure (a tank) for dyeing cotton cloth. During the Dutch period Sadras became a centre of high-quality cloth manufacture. The area from Pondicherry to Pulicat was home to the best cotton textile painters of the Coromandel Coast. One historian has argued that they could accurately reproduce designs given to them including European coats of arms that the printers would faithfully reproduce. Pieter van Dam at the end of the seventeenth century wrote that “the best [textile] painters of the Coromandel Coast were to be found at Sadraspatnam, both because of the neat way they handle their painting, and because of the pure water there, which gives everything the best sheen and fastness that cannot be imitated in other places” (vol. 2.2, GS76, p. 205). By this date, Sadras was considered a hub for the production of the best Coromandel textiles, most especially large palampores that were fashionable in the Netherlands.

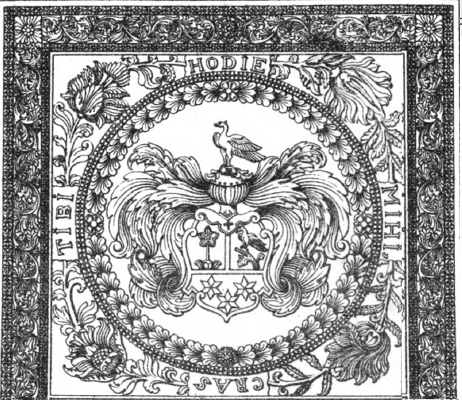

European Coats of arms are also a motif across a different medium. From cloth to stone, they tell us about the challenging lives and the early deaths of some of Sadras’ inhabitants. Best preserved within the fort complex is a cemetery that hosts around 20 graves of Dutchmen and women who lived and died in Sadras between the 1620s and the late eighteenth century. These tombstones might have been carved by local stone cutters, an occupation for which the Sadras area is still well known. The beautiful lettering and superbly-carved coats of arms of these tombs are tarnished by time and weather but they still allow us to decipher the lives and deaths of its occupants.

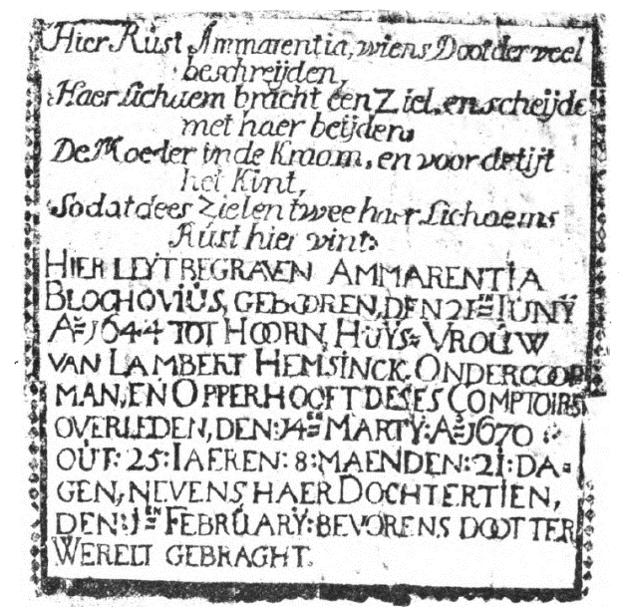

Most impressive is the gravestone of Ammarentia Blockhovius (1644-1670), wife of Lambert Hemsinck who for twenty years between 1668 and 1688 was the chief (opperhoofd) and junior merchant at Sadras. As the gravestone tells us Ammerentia died at the age of 25 years, 8 months and 21 days on the 1 February 1670 in childbirth and lay “next to her daughter”. Another son had died in infancy at Palacole (Palakollu) in 1761. Another of her sons was to die age sixteen as the upper part of the gravestone tells us:

Hier legt begraven PIETER HEMSINCK jongman geboren ten

desen contoire Zadrangapatnam den 3en Augusti 1665,

overleden den 24en February 1682. Out zynde 16 jaren ,

6 maenden , 21 dagen.

Here lays buried PIETER HEMSINCK young man born

at this factory Zadrangapatnam on the 3rd of August 1665,

died on the 24 February 1682. He was 16 years old,

6 months, 21 days old.

We know little of Ammarentia apart from the fact that she came from a ‘global’ family, her father Petrus Dirksz Blockhovius (1610-1649) having died in Japan when Ammarentia was just 5 years old. More instead is known about her husband Lambert whose 20-year tenure at Sadras ended with a corruption enquiry. He is not buried locally: together with another son, he left in 1686 for Batavia to escape possible prosecution but also the anger of locals who had plundered his house in revenge for him having abused his concubine. Written sources reveal that Lambert Hemsinck had no less than 33 slaves, providing a small glimpse into the lives of the non-Dutch population who lived in Sadras.

Bibliography

Lucas Ausems, ‘Hendrik Adriaan van Reede tot Drakenstein and his Committee of redress in Coromandel (1687-1690)’ MA(res) Thesis in Colonial and Global History, Leiden University, 2021.

Julian James Cotton, List of Inscriptions on Tombs or Monuments in Madras Possessing Historical or Archeaological Insterest. Madras: Government Press, 1905.

Ebeltje Hartkamp-Jonxis, 'Indian chintzes with Dutch coats of arms (1725-1750)', Oud Holland 134/1 (2021), 49-68.

Paul M. Mason, ‘Two 17th-century English factories in North Kanara, Karnataka, India: a historical archaeology perspective’, Post-Medieval Archaeology 50/2 (2016), 227-243.

Alexander Rea, Monumental Remains of the Dutch East India Company in the Presidency of Madras (Madras: Government Press, 1897).

W. Stapel et alt, Pieter van Dam’s Beschrijvinge van de Oostindische Compagnie 1639-1701, The Hague 1927-1954.

T.S. Subramanian, ‘Unravelling a Dutch past’, The Hindu, 23 May 2003: https://frontline.thehindu.com/other/article30216982.ece