Delimiting the Factory in the Atlantic World

In 1719 Daniel Defoe, writing under his pen name Andrew Moreton, published The Just Complaint of the Poor Weavers Truly Represented. The treatise advocated the introduction of import controls to protect England's weavers from Indian textiles (a subject to which Defoe turned his attention on at least one other occasion; see Defoe, The Indian Trade Calmly and Critically Considered). In one section of the The Just Complaint Defoe vociferously lambasted a writer who had maintained that most of the calicoes brought into the country were constructed in England's "OWN COLONIES in the East-Indies." After making a few jabs at his interlocutor, Defoe went on to say:

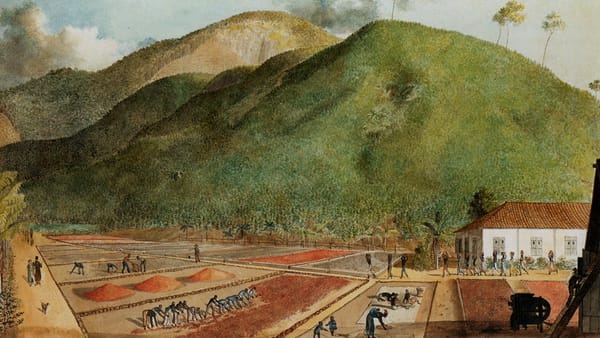

"The true Case is, that this poor ignorant Writer, does not understand the difference between a Colony, and a Factory; and that there is no such Thing as a British Colony in the East-Indies. Had we a Colony there, such as New England, New York, Barbadoes, &c. are in America; where the English People being planted, the Callicoes were made by the King's own Subjects, and the Cotton was the produce of the Land in the said Colony; where the said Land is always reckon'd a Part of his Majesty's Dominions; and where the Natives are the King's Subjects, tho' not English, as the Slaves are in our Colonies of Jamaica, Barbadoes, and other Places; had we, I say, such Colonies in the East-Indies, more had been to be said for the Callicoes made there.

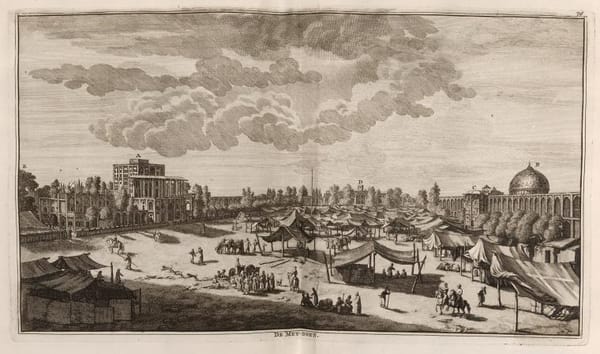

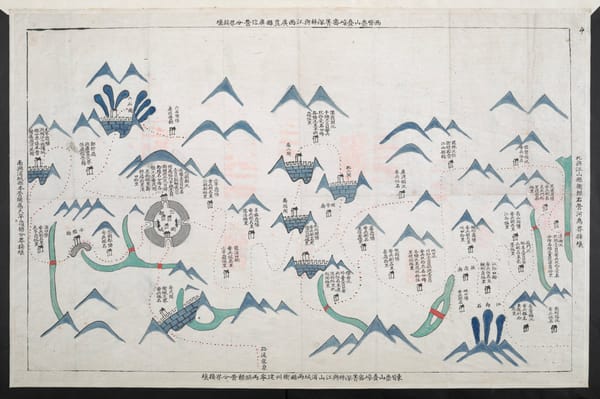

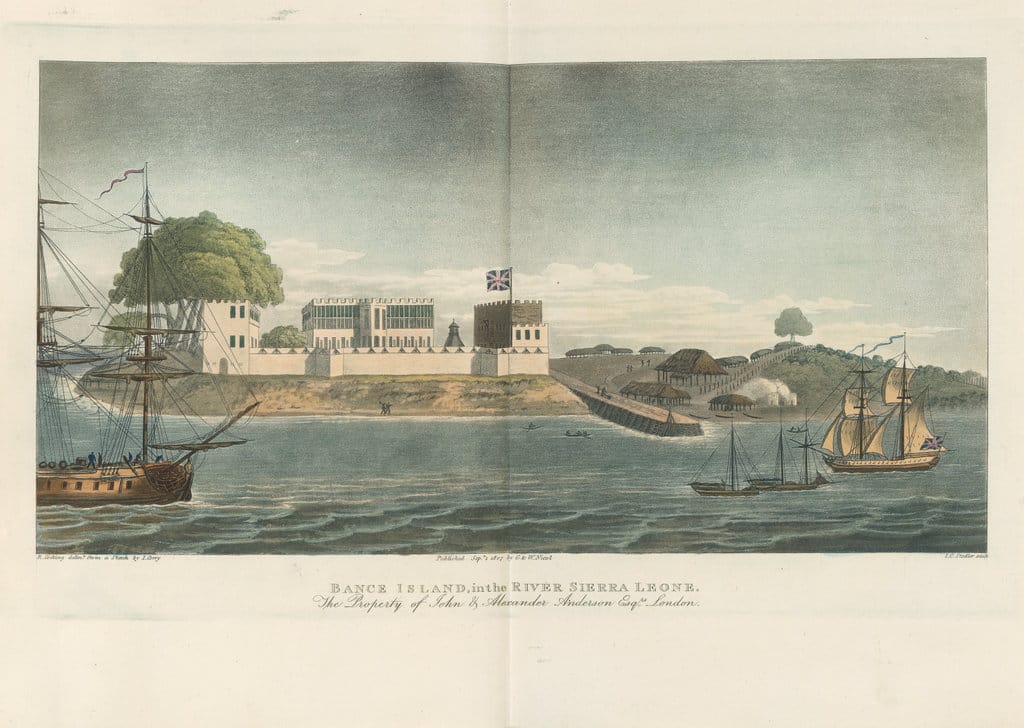

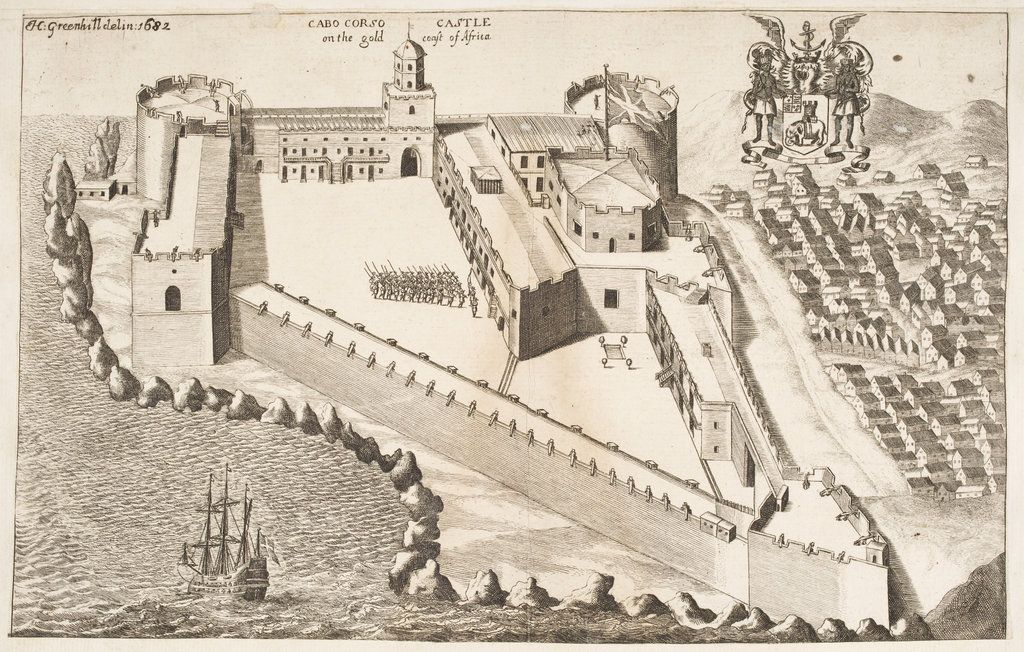

But the Nature of a Factory is quite another thing; for a Factory is no more than a Settlement for Commerce by the permission of the King, or Government, or People of the Country; It is true that sometimes Forts and Strengths are built in such Countries, either by Permission of the Governour of those Countries, as on the Coaft of Malabar, Coromandel, Sumatra, and other Places in India; or by Force, as on the Gold Coast in Africk; but in neither of these is there any Colony, much less any Manufacture made there by our own People." (Defoe, 17-18)

This call for the abandonment of mere trading factories in favor of a model of formal empire in the East Indies is noteworthy in itself. But Defoe's remarks also capture well the geographic delimitation of the early modern factory; for as he pointed out, with the exception of West Africa, the term was not widely used in the Atlantic world. Instead, as outlined in another blog post on our site (What is a Factory?), the factory had acquired a strongly, if not wholly, Indian Ocean/Asian maritime dimension by the first quarter of the eighteenth century. And though many of the factories in West Africa were constructed by force in the interests of expanding the Atlantic slave trade, the correspondence of regional European factories in the late seventeenth and early eighteenth centuries clearly shows a reliance on the good graces of local rulers, as was the prevailing arrangement in most parts of Asia in that same period (Law ed., The English in West Africa: The Local Correspondence of the Royal African Company of England).

Even so, in the West African case, there appears to have been a much stricter division between the factory and the fort than in the late seventeenth and early eighteenth-century Indian Ocean. What is more, the loss of the Royal African Company's monopoly at the tail end of the seventeenth century, which led to a boom in private trade, ensured that the factory possessed a status in the framework of European commerce in West Africa unlike that on offer in the Indian Ocean. As a statute promulgated by the English Parliament at the time had it:

"XXXV. All the Natural born Subjects of England Trading to Africa and paying the Duties by this Act imposed, shall have the same Protection for their Persons, Ships and Goods, from the said Forts and Castles, and the like freedom for their Trade as the said Company, and their Ships and Goods have: And all Persons Trading to Africa and paying the Duties as aforesaid, may at their own charge settle Factories on any part of Africa within the limits aforesaid without let of the said Company. And all Persons not Members of the said Company, so Trading and paying the said Duties Tall with their Ships and Goods be free from all Molestation, Penalties or Impositions from the said Company, by reason of their so Trading." (A Continuation of the Abridgment of all the Statutes of K. William and Q. Mary, and of King William the Third, in force and use. Begun by J. Washington ... and now further continued, from the beginning of the second session of the Third Parliament, 20 October 1696 to the end of the third and last session of the said Third parliament, 5 July 1698, 160).

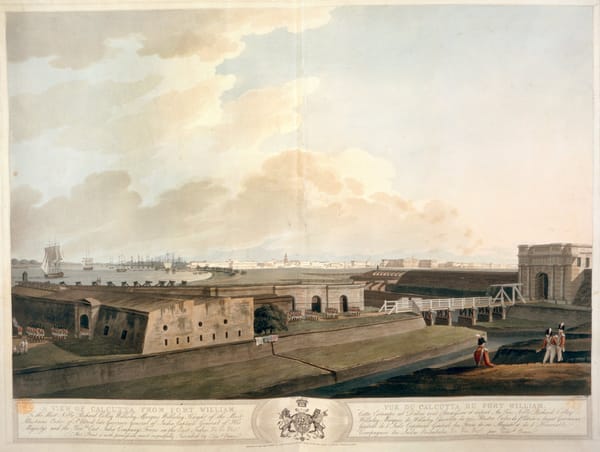

This abrogation of the Royal African Company's monopoly stood in distinct contrast with the perpetuation of monopoly of the East India Company (EIC) into the early nineteenth century. In the case of the EIC, no factory could be established by private traders. Instead, the creation and closure of factories was closely monitored by the Court of Directors in London and private trade was closely monitored and often frowned upon.

The near absence of factories in the contemporary Western Atlantic and their disparate character in the Eastern Atlantic says much about the disparities in the structure of oceanic trade in this era. It is telling, for example, that in his well-known treatise on the West Indies, Sir Thomas Dalby called for a “Common Factory” to be established in the territory, in addition to a separate company (Thomas Dalby, An Historical Account of the Rise and Progress of the West-India Collonies, and of the Great Advantages They are to England, in Respect to Trade (London: Golden Ball, 1690)). In the Indian Ocean, by contrast, the establishment of a factory would have been second nature, even a sine qua non. Undoubtedly, too much can be made of distinctions: Batavia or Goa shared a good deal with the Western Atlantic insofar as they were instantiations of direct European territorial control in Asia. Having said that, there were plenty of factories in Asia where Europeans were the minor players, as Defoe's polemic represented so well. In the end, even the EIC recognized that its factories were no substitute for the benefits of formal colonies.

Sources

A Continuation of the Abridgment of all the Statutes of K. William and Q. Mary, and of King William the Third, in force and use. Begun by J. Washington ... and now further continued, from the beginning of the second session of the Third Parliament, 20 October 1696 to the end of the third and last session of the said Third parliament, 5 July 1698 (London: Charles Bill, 1699).

Thomas Dalby, An Historical Account of the Rise and Progress of the West-India Collonies, and of the Great Advantages They are to England, in Respect to Trade (London: Golden Ball, 1690).

[Daniel Defoe], The Just Complaint of the Poor Weavers Truly Represented... (London: W. Boreham, 1719).

Robin Law ed., The English in West Africa: The Local Correspondence of the Royal African Company of England, 3 parts (Oxford: Oxford University Press/British Academy, 1998-2007).