Understanding “Aunth” (આન્ટ) in the 18th century: perspectives on money and credit from the EIC factory in Surat

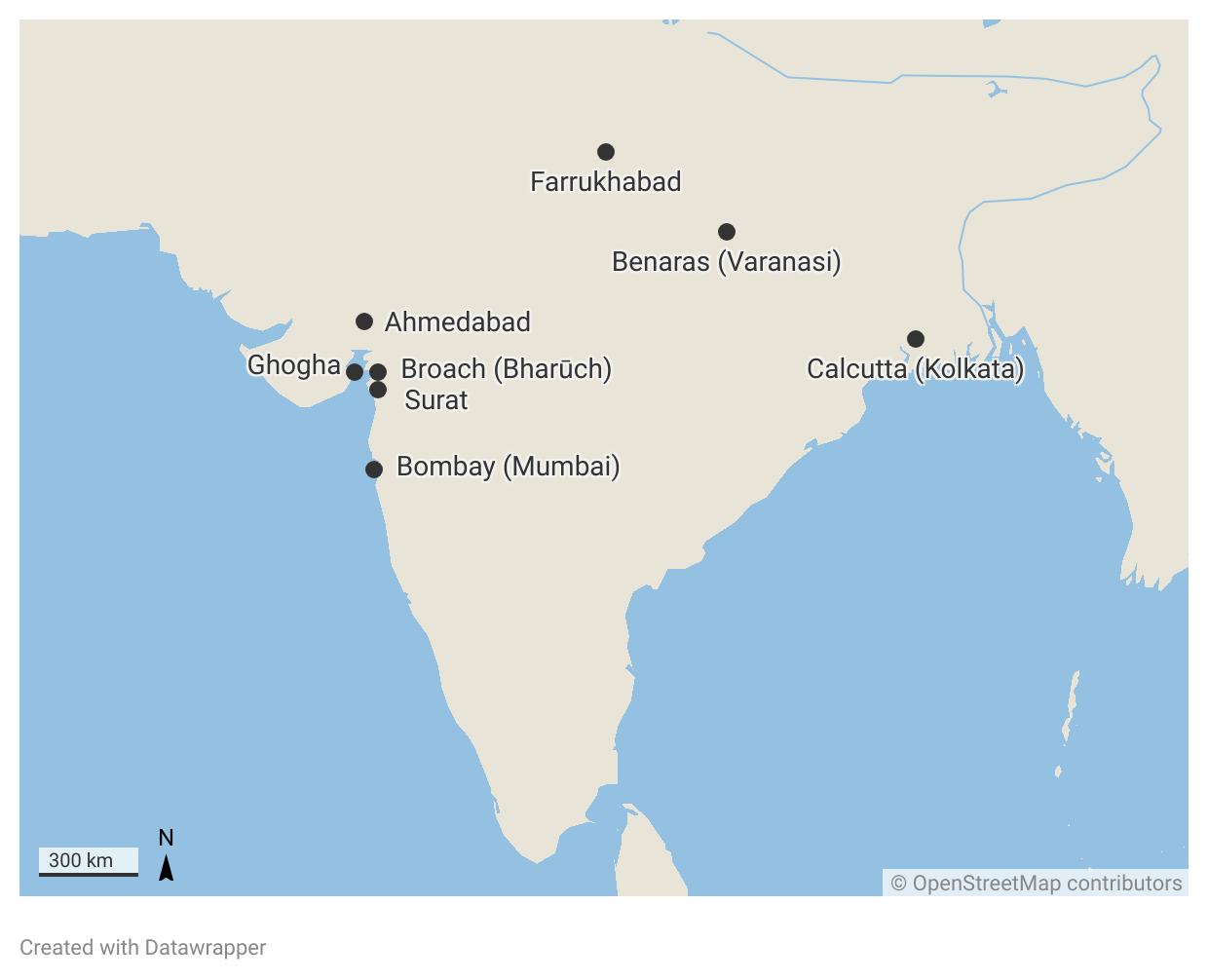

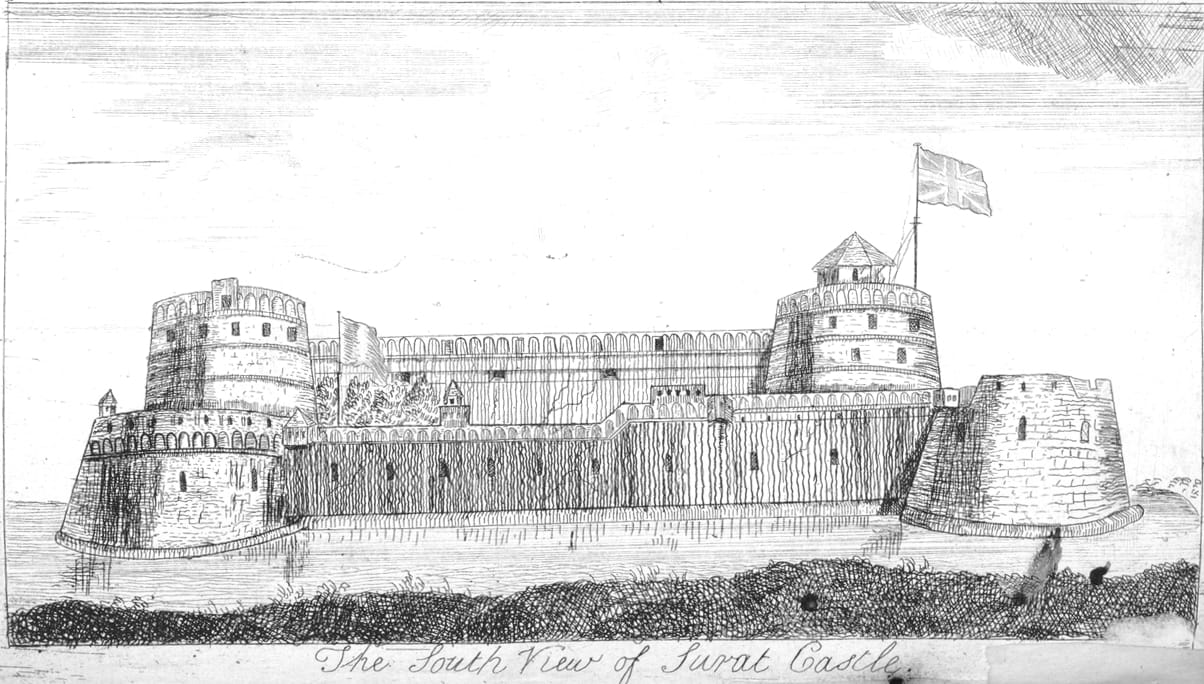

Established in 1612, the Surat factory oversaw a network of agencies at Gogha, Ahmedabad, Broach, Bombay and overseas at Gombroon and Basra. These agencies were important in ensuring steady and regular supplies of textiles and export items for the English East India Company’s (EIC) official investment. These agencies also helped the Surat factory to collect and compile information on textiles, money market and indigenous credit practices that came in for scrutiny and occasional regulation. One such practice was the આન્ટ.

What was this practice? H.H. Wilson’s A glossary of judicial and revenue terms and of useful words occurring in official documents relating to the administration of the government of British India from 1855 defines it as a cash transfer, a fictitious currency or book credit in which bills of exchange and dealings in articles of trade could be paid at the option of the holder, varying according to the exchange of the day and the value of the coin in which the amount is computed. The Surat factors encountered it from very early days, but it was from the middle decades of the 18th century that it became pervasive enough for the Surat factory authorities to step in to investigate the phenomenon, and by extension to understand the money market better.

Some preliminary observations on the money market are in order here. Surat was the major port of the Mughals drawing in huge amounts of treasure from overseas trade. Much of the silver was coined in the imperial mint but the long queues during peak season meant that merchants were forced to approach private but licensed bankers to convert bullion into legal tender. For the greater part of the seventeenth and first quarter of the 18th century, the Mughal regnal coin held its own and dominated all commercial transactions. The volume of money in circulation determined the interest rates at which loans could be raised while the scale of trade between regions determined the rate of exchange for bills of credit or hundis as they were known. The hundis were an important medium of remitting proceeds and profits as well as raising money for financing trade at a given centre. Hundi rates appear to have been standardized if we are to go by the detailed observations of the French visitor Jean Baptiste Tavernier (1605-89).

The money market was seriously disrupted in the wake of the 18th century crisis, when the decline of the Mughal Empire and the rise of regional states impacted trade and commercial flows and also gave rise to local currencies that regional dynasts issued. This meant that calculating the rates of exchange between one coin and the other and speculating in them became rampant. The Surat factors had occasion to comment on this even before this period, but from the 1770’s the scarcity of specie, debased coinage and the fluctuation in exchange rates between different kinds of coins in circulation became recurrent motifs in factory documentation.

The problem of a debased coinage and fluctuating exchange rates was especially challenging for the EIC’s Surat and Bombay factories. The depressed level of trading activity by the English Company and the political rivalry of the Marathas in the region made the Bombay Presidency vulnerable and dependent on handouts from the Calcutta factory. The remittances were mediated by the indigenous credit network operated by local bankers of Surat. The latter invested in inter-regional trade; the Bengal-Bombay traffic in cotton and silks was the principal artery for their money flows. Consequently any trade disruption in this sector was bound to impact exchange rates between Surat/Bombay and Bengal. Political competition and instability were no less significant. The formal induction of the EIC into the political system of Surat (1759) necessarily meant that currency affairs became an integral part of governance and sovereignty. The issue of an enhanced exchange rate, referred to as batta or ‘aunth’, was seen to fall under the jurisdiction of the reigning Nawab of Surat who after 1759 was but a junior partner in the city’s governance. The English Company as qiladars of Surat after 1759 used their newly acquired political clout to familiarise themselves with money matters.

In 1770, the Surat factory set up a committee to enquire into the issue of fluctuating ‘aunth’. The committee met with the ruling Nawab of Surat who insisted that the high exchange rate that he referred to as (batta) on the Surat rupee was not a new thing and that it had been the practice of the shroffs or bankers to practice it. He also insisted in the meeting that money was scarce in Surat not because the shroffs were manipulating the exchange but because the mint had suspended operations and because a huge volume of Surat rupees on account of their intrinsic purity and quality had been exported elsewhere. The nawab also maintained that bankers could not be coerced to reduce the batta or discount. In the following years, the problem of a high discount persisted although there was some confusion about who participated in the business. Bankers with a reputation and who had access to larger reserves seem to have refrained from exploiting minute differences in exchange – in 1767, the Surat Council drew attention to the abuses by petty shroffs who refused to receive certain rupees in the bazaar and manipulated the situation in raising exchange rates. In this case too, it was pointed out that the practice of discounting coins at a disproportionately high exchange rate crisis was largely on account of the diminished volume of money in circulation in western India.

Predictably both parties in Surat, the Nawab and the English Company made it a political issue citing a case of bad governance and relating the scarcity of money to poor working of the mint. The nawab on his part, while admitting that the mint needed immediate reform also hinted the drawing away of silver by the English factors and private traders and suggested that a general duty of 3% be levied on all silver exports, thereby indicating that duties extracted at the various custom houses (Phurza or Mughal custom house, Latty or English custom house) needed rational equalization. Nothing came out of these deliberations – in 1789, the principal banker of the Company, Tarwady Arjunji the city’s leading banker pointed out how the Surat rupee commanded high standards, how high mint charges deterred merchants from getting the bullion and encashing it for current rupees, and how it was imperative for the nawab to reduce duties on mint charges to prevent silver from going to other mints. Whether the senior banker meant this to be a mild threat to persuade the Nawab to reduce minting charges and, thereby act as proxy, for the English company is not clear but what is evident is that by the 1780’s, the exchange business as a consequence of multiple currencies circulating within regional economies was a sizeable one. The requirements of trade and of extensive state financing were met by a dense cluster of inter-related credit transactions and transfers, commented on by contemporaries. The practice of ‘aunth’ resurfaced in this context giving rise of debates and discussions among the personnel of the English Company, some of whose officials recognised this to be notional money accounts that enabled rational adjustment of accounts. Subsequently the practice became part of a larger assemblage of operations that were devalued, if not de-legitimized as speculation and gambling.

Such a characterization obscures the complexity of procedures connected with indigenous trade and banking as well as the risk-sharing strategies that indigenous capital was able to adopt during the time of transition in the 18th century. We come across this practice described extensively by Ali Mohammed Khan in his Mirat I Ahmadai (A History Of Gujarat; 1761), who referred to the disproportionate increase in the aunth rate, almost as high as 20% forcing the Diwan Muhtarim Khan to summon the city’s Nagarshet Kapurchand to intervene pointing out that mutual transactions of people had come to a standstill. There were no cash dealings among the people and it was time that bankers came together to stop the practice. By this time, according to him, trade in hundis had become so pervasive that cash ceased to enter any stage of the transaction leading to speculation, hardships and severe cash crunches.

As long as the circulation of hundis kept pace with the volume of money in circulation, the exchange rate found its level and did not create either uncertainty or distress. It was when the conditions changed that the rate of exchange went up and encouraged trade in credit transfers or ‘Aunth’ that problems arose and concerns were voiced. As long as the hundi worked as a negotiable financial instrument, it was seen as useful but when it became part of exchange manipulation during times of commercial and financial stress, it became a matter of administrative scrutiny. This was evident in the second half of the 18th century, a testing time for merchants and rulers, when political fragmentation, the long-term decay in the Indian Ocean trade and the circulation of multiple currencies created confusion that bankers were able to exploit. What was episodic in the seventeenth century became endemic in the 18th and in the years between the dismantling of the Mughal imperial system in Gujarat and the establishment of the rule of the English East India Company, the problem of exchange manipulation became serious. Was this simply a manifestation of rapacious extraction and manipulation, or was it a practice to help distribute risks in a desperate situation?

The answer may lie in the peculiarity of the eighteenth century when in the wake of regionalisation of power, multiple coins circulated in western India and which forced the EIC factories in Surat, Broach, and Bombay to address the situation more proactively. Exchange rates between diverse coins were determined by trade balances and bullion availability in the market. However, that asymmetric trade balances existed and that the requirements for money transfers exceeded available supplies necessarily meant that sarrafs in the business held the upper hand.

The issue of exchange manipulation re-surfaced in the late 1780’s both in relation to the local situation in Gujarat as well as in relation to the larger money market connecting western India with the heartland. The factory authorities in Surat made repeated efforts to maintain a good state of coinage and retain the Surat coin as the acceptable standard. It was also at this time that they began to examine the issue of the “aunth” more closely and even abolished it temporarily in 1795, with the consent of some bankers. These were bankers whose interests differed from that of the Bengal shroffs who were the principal gainers in the exchange business and exploited the difference in rates. By this time, it would also appear that the ‘aunth’ had acquired new dimensions as a practice that sarrafs carried out in their internal dealings.

The trade in “aunth” drew the attention of the Company authorities during the late 80’s and 90’s when there was an unprecedented expansion in the volume of remittances and hundi transfers between Bengal and western India via Benaras (Varanasi). Exchange rates fluctuated and notwithstanding protracted negotiations, the bankers insisted on their terms. They operated from a vantage point of relative strength; they imported bullion largely to supply merchants with provisions from the interior for which they received bills of exchange on Calcutta and which were subsequently invested in bullion. Upon any sudden demand for ready money, the exchange between Calcutta and the interior became very high. The Company authorities, however, were of the opinion that even if the Calcutta Rupee became the legal tender, the exchange rate would not necessarily be favourable given the intrinsic difference in the value of the Benaras and Farrukhabad rupee and maintained that shroffs offered good competition and were not to be blamed for fluctuations. We have the case of a deposition from the agent of a principal banker in 1788 where he stated that in virtually all their dealings with the Company, shroffs dealt in ready money, while in their own dealings, they practiced ‘aunth’ which was an imaginary value. The aunth was generally better or more valuable than the coin in current circulation so much so that by paying or transferring 100 rupees of aunth from one banker to another, the negotiator or shroff who wanted the ready money would receive from the other banker 107 or 108 rupees in coin. Only during times of war when there was a great demand for ready money, the value of ‘aunth’ would go down, so much so that 103 or 104 aunth would produce only 100 rupees in coin. This was the reason why there was a marked difference in rates of exchange as well. What was evident from the deposition was that speculation in exchange trading as aunth was practised among bankers and that this did not apply to the operation of the Company’s business whose annual demands were met by ready money under the permissible exchange rates.

The Company authorities were not ill disposed to the speculation as such even if in 1796 in Surat they endorsed the decision to ban the practice when some shroffs complained of consequences of speculation in exchange for inferior coins. On 5 April 1795, the Mahajan of the Surat shroffs Vanarasidas Jaidas gave in writing to the Surat chief that all Surat rupees old and new and barring some specific coins would pass current. During the proceedings, the Chief informed his superiors that the Bengal shroffs (i.e. those who transacted the silk-cotton traffic) profited most by the ‘aunth’ (exploiting the demand for bills in the sector) and that it was oppressive to other shroffs. The petition put out that more than five thousand of them had suffered from the excessive speculation in exchange that had to be brought down.

Some of the EIC factory officials in Surat who looked into the matter were not entirely convinced of the complaints - Mr. Cherry for one, saw the practice as a convenient mode of raising money by credit or transfer. In his view, the ‘aunth’ was nothing but the value of money combined with the confidence reposed in it, and in the credit of those who carried on a trade in it. Its efficacy rested on the creditworthiness of those who transacted the business and on the volume of bullion in the market. He maintained that it was of great utility in commerce in a variety of ways and could not fail to contribute in facilitating the negotiation of bills of exchange affording a convenient medium by which an interchange of value could be affected without the necessity of procuring ready money. This, he insisted, was especially useful in a region where there was a great demand for cotton and where transportation was risky and which made credit transfers extremely useful. Mr. Cherry admitted that speculation unchecked could be injurious but that it appeared wrong to deprive the public of the general advantage and convenience of the “aunth’ in consequence of ‘the partial evil arising from the effects produced by rash men’.

References

Irfan Habib, Trade and merchants in Indian history, Published online 2015. https://doi.org/10.1177/2348448915577295.

Najaf Haidar “Precious metal flows and currency circulation in the Mughal Empire”, Journal of the economic and social history of the Orient, Vol.39, No.3, 1996.

Lakshmi Subramanian, “Merchants in transit Risk sharing strategies in the trading world of the Indian Ocean” in H.P. Ray (ed.), The Indian Ocean 1500-1800. O.U.P., Delhi, 2006.

On the author

Lakshmi Subramanian is a retired Professor of History, Centre for Studies in Social Sciences, Calcutta. Her research and teaching interests span from Indian business history to the social history of music and performance in the subcontinent. She has many publications to her name, the latest of which is India before the Ambanis: A history of Indian business, market and economy (2024). She is member of the advisory board of CAPASIA.