The Chinese in Nagasaki and Japanese Systems of Trade Control

In the early modern period, the city of Nagasaki, located on the northwest coast of Kyushu Island, served as Japan’s primary port for international trade. Throughout the Edo period (1603-1868), foreign trade and diplomatic relations were also conducted through three other regions, each administered by a local domain: the Shimazu family of Satsuma, who managed relations with the Ryukyu Kingdom; the Sō of Tsushima, responsible for interactions with Korea; and the Matsumae, who oversaw trade and diplomacy with the natives in Ezo (present-day Hokkaido). Collectively, these four channels are known as the “four gateways” (yotsu no kuchi 四つの口), a concept articulated by historian Arano Yasunori in his critique of the national seclusion (sakoku 鎖国) paradigm, according to which, in this period, Japanese trade and interaction with the rest of the world were severely limited. Among these, Nagasaki held a distinguished status. It was the only gateway directly governed by the central government—a status held since its incorporation into the tenryō 天領 (heavenly territory, i.e., national demesne) by the “Great Unifier” of Japan, Toyotomi Hideyoshi, in 1587. Also, from the mid-seventeenth century onward, Nagasaki was the sole site where the Tokugawa Bakufu (military government) permitted foreign merchants to engage in trade.

Typically, when discussing foreign merchant communities in Nagasaki, scholarship has often focused on the Portuguese and the Dutch, who indeed played a crucial role in the city’s development. The port was established in 1571 following negotiations between Jesuit missionaries—who travelled to the Japanese archipelago with logistical and financial support from the Portuguese—and the local lord (daimyō 大名), Ōmura Sumitada (baptised Bartolomeu). Its purpose was to serve as a port of call for Portuguese ships arriving from Macau, which primarily transported Chinese raw silk, and to provide a safe haven for Japanese Christians fleeing persecution from other domains. For several decades, this aim was fulfilled: the city hosted a robust native Christian community, and the port was visited almost annually by Portuguese-captained ships from Macau.

In 1639, the Portuguese were banned from Japan by a decree issued by the third Tokugawa shogun, Iemitsu. Two years later, the Dutch were relocated from the port of Hirado to Dejima, an artificial island constructed in Nagasaki in 1635. By that time, the English and Spanish, who had also attempted to establish trade relations with Japan in the late sixteenth and early seventeenth centuries, had already been banned by the Tokugawa shogunate. Thus, the Dutch were the only Europeans permitted to trade in Japan until the mid-nineteenth century. However, they were not the only foreigners conducting trade in the archipelago, or even in Nagasaki. Since the port’s very founding, another merchant community had been active in the town: the Chinese.

The Portuguese in East Asia famously capitalised on the disruption and eventual suspension of official Sino-Japanese trade in the mid-sixteenth century. Prior to this, a long-standing and flourishing tradition of trade and diplomatic exchange had existed between the two countries. The Ming dynasty (1368-1644), upon its rise to power, sought to channel all foreign trade through its tributary system and the corresponding “tally trade” (kangō bōeki 勘合貿易). Under this framework, Japan dispatched nineteen licensed trading missions to China between 1404 and 1547. However, the weakening control of both the Ming court and the Japanese Muromachi Bakufu (1336-1573) over their peripheries and maritime borders in the fifteenth and early sixteenth centuries led to the rise of outlaw groups who engaged in unlicensed trade and piracy. These groups, known as the wakō 倭寇, are typically described as pirates who raided and traded along the coasts of Japan, China and Korea. Although the wakō consisted of both Chinese and Japanese members, their raids on Chinese coastal settlements and the shelter they received from profit-seeking Japanese warlords in Kyushu prompted the Ming court to hold Japan responsible. Consequently, China banned all official trade with the archipelago in 1547.

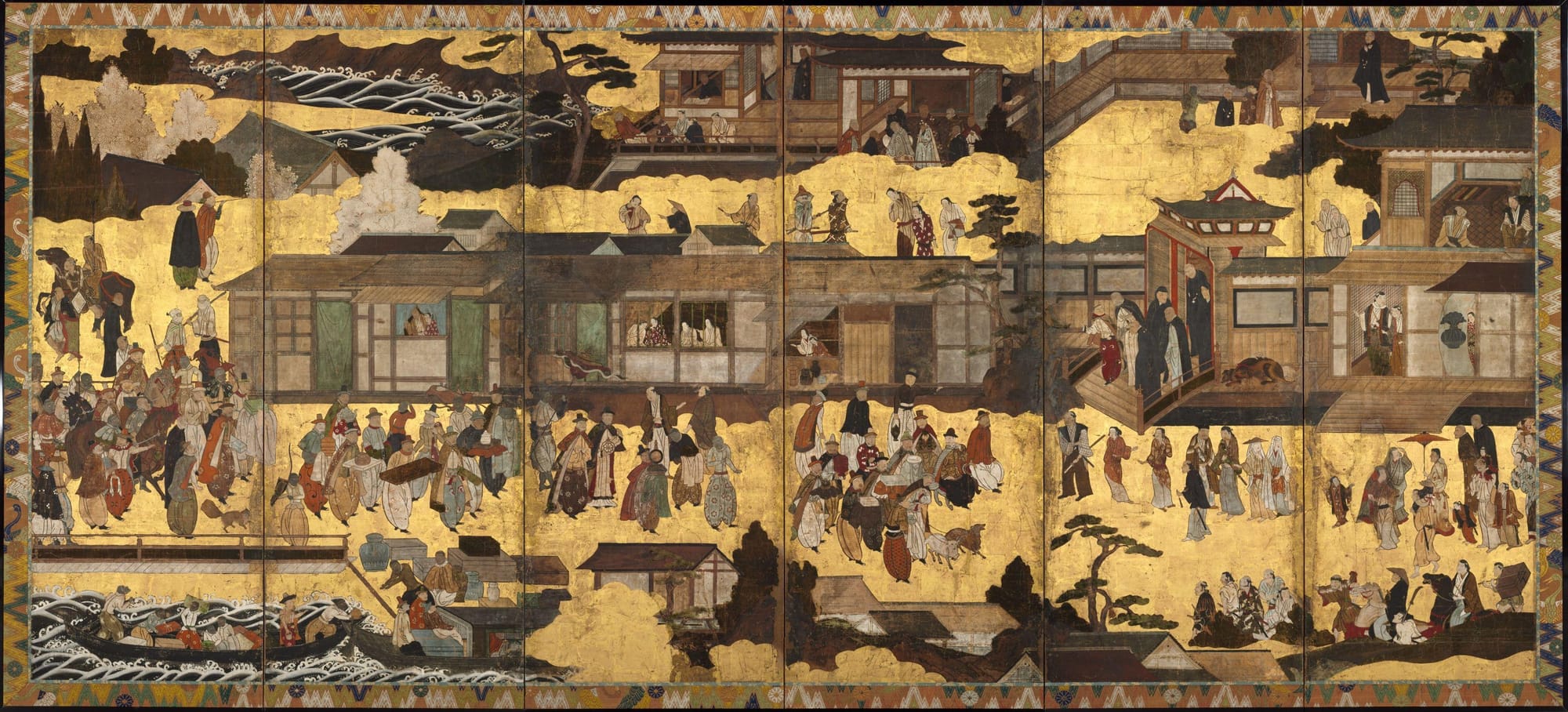

It was under these circumstances that the Portuguese arrived in Japan and ultimately engaged in the Sino-Japanese trade, via the Macau-Nagasaki route. Notably, they did not create new trade networks but instead relied on routes established by these illicit maritime bands. By this time, Chinese merchants engaged in clandestine commerce had established a few bases in Kyushu. In 1543, the first Portuguese individuals reached Japan aboard a Chinese wakō junk that had drifted off course and landed in Tanegashima. Among those onboard was Wang Zhi (d. 1559), who had established operations in Hirado and the Gotō Islands. These locations soon became popular stops for Chinese ships and Japanese merchants.

When Nagasaki was designated as a port of call for Portuguese merchant vessels, Chinese groups also started trading there. Unlike the Portuguese – subjects of a crown that monopolised the trade voyages to Japan through the Estado da Índia – the Chinese were independent traders, viewed as outlaws by their homeland authorities. In Nagasaki, they were permitted to reside, marry, and establish families. Many were employed by local Japanese lords to conduct business, which further increased immigration. After Toyotomi Hideyoshi completed his military campaigns in Kyushu and seized control of Nagasaki from the Jesuits, he initiated a form of vigilance over the Chinese community, while simultaneously employing many as interpreters and informants during his expeditions to Korea (1592-98), which ultimately targeted China.

Following Hideyoshi’s death in 1598, the Japanese army withdrew from Korea, ending the conflict. In 1600, Tokugawa Ieyasu emerged as Japan’s new military leader. He sought to restore peaceful relations with China and dispatched an envoy to the Ming court that same year in an attempt to reinstate the tally trade. Although initial negotiations seemed promising, they ultimately failed to resume official trade relations. Ieyasu, in turn, adopted a welcoming stance towards Chinese merchants in his early years in power, authorising Chinese ships to dock at any Japanese port in 1604. Nevertheless, the Tokugawa shogunate worked to concentrate merchant activities in Nagasaki. As a result, the city grew in prominence, gradually consolidating its position as the archipelago’s principal trading hub.

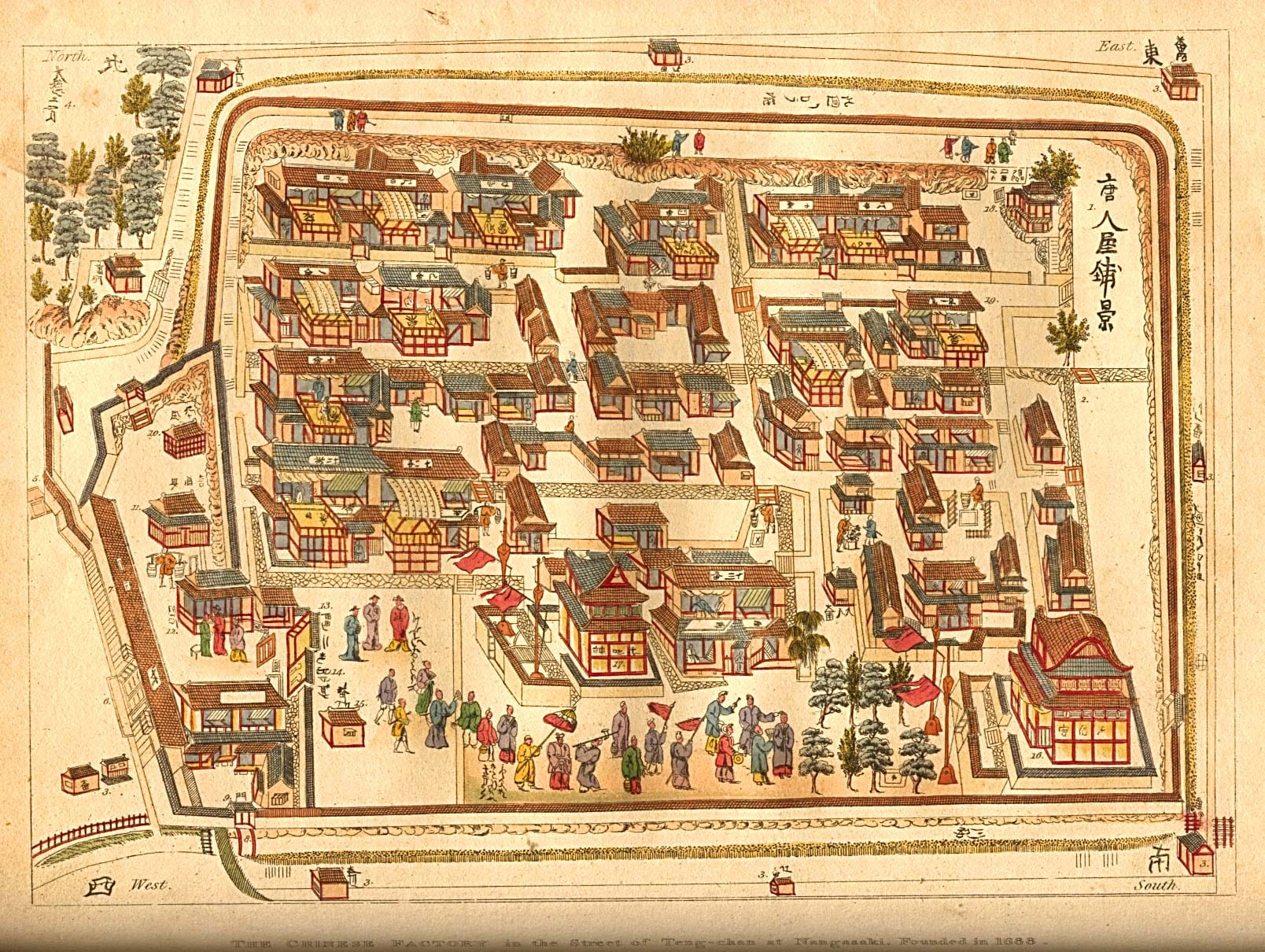

Despite Ieyasu’s apparently open policy, his underlying aim was to bring private maritime activity under government control. A few months after his death in 1616, a decree was issued restricting foreign ships to the ports of Hirado and Nagasaki. However, an addendum to the decree specifically exempted Chinese vessels. Despite this exemption, the activities of Chinese merchants were increasingly monitored and brought under the jurisdiction of the Nagasaki magistrate. In 1635, Chinese ships were finally confined to Nagasaki, while the Portuguese were relocated to the newly built artificial island of Dejima. In 1639, the Portuguese were expelled entirely, and two years later, the Dutch factory was transferred from Hirado to Dejima. Although the Chinese continued to reside in the city, after 1636, they were no longer allowed to marry Japanese women and live among the general populace. They were instead moved to a hillside facing the bay. This settlement, formalised only in 1688-9, marked the beginning of the Nagasaki Tōjin Yashiki 長崎唐人屋敷, the Chinese quarter.

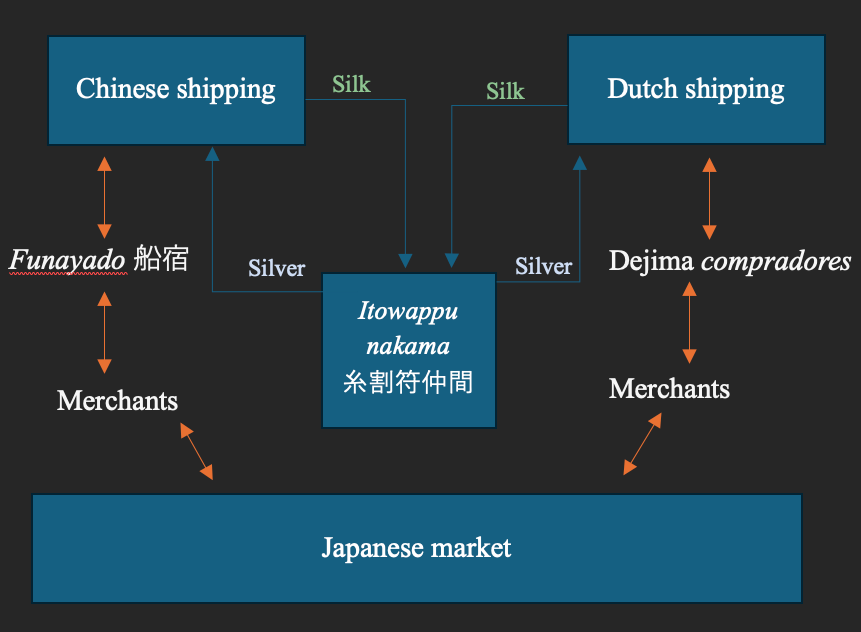

In Nagasaki, the Dutch were confined to Dejima, while Chinese ships docked in the city at the funayado 船宿, a type of inn for sailors and their junks. These establishments not only offered accommodation but also various trade-related services, including warehousing, transaction mediation, and the procurement of export goods. From 1604 to 1655, all imported raw silk had to be purchased by the Japanese itowappu nakama 糸割符仲間 (guild of raw silk thread importers) merchant association, which then redistributed the merchandise to the domestic market. Other goods, however, were negotiated either through these inns, whose owners acted as brokers, or, in the case of the Dutch in Dejima, via the compradores (from the Portuguese word for “buyer”).

Before annual price negotiations for raw silk commenced between the itowappu nakama members and the foreign merchants, the Bakufu and a select group of daimyō were granted the privilege of purchasing a fixed percentage of the goods. In 1655, the association was dissolved due to its failure to prevent the rise in silk prices. This dissolution increased the profits of funayado owners, particularly the major ones, who began to dominate business operations. To counter this concentration of power, the yadochō-sei 宿町制 (lodging ward system) was introduced in 1666. Under this system, the neighbourhoods of Nagasaki (excluding Dejima and the licensed “pleasure quarters”) took turns serving as funayado.

When the Qing dynasty lifted its maritime ban in 1684, the number of Chinese merchant ships arriving in Nagasaki surged, driven largely by demand for Japanese copper. To prevent the depletion of precious metals, the Tokugawa shogunate imposed a limit on the total value of trade and the number of Chinese ships allowed to dock annually. In 1688, the Chinese quarter, the Tōjin Yashiki, was officially established, and the lodging function previously held by the yadochō was transferred there.

The Tokugawa shogunate and the Qing dynasty never resumed the tally trade. The Chinese merchant community in Japan operated independently from both the Ming and Qing courts, offering an alternative to the official trade under the tributary system. Additionally, the commercial networks maintained by Satsuma with Ryukyu and by Tsushima with Korea provided other indirect avenues for Sino-Japanese trade during the Edo period. This multifaceted approach allowed the Tokugawa shogunate to remain outside the Chinese Sino-centric tributary system framework while sustaining crucial trade with its major neighbour.

Further reading:

Arano, Yasunori. "Kinseichūki ni okeru Nagasaki bōeki taisei to nukini (mitsubōeki): Kaikin-ron no ichireishō to shite [近世中期における長崎貿易体制と抜荷 (密貿易): 海禁論の一例証として.] Shien, 70, no. 1 (2009): 95-117.

Cullen, Louis. ‘The Nagasaki Trade of the Tokugawa Era: Archives, Statistics, and Management’. Japan Review 31 (2017): 69–104.

Hesselink, Reinier H. ‘I Go Shopping in Christian Nagasaki: Entries from the Diary of a Mito Samurai, Ōwada Shigekiyo (1593)’. Bulletin of Portuguese - Japanese Studies II, no. 1 (2015): 27–45.

Kisaki, Hiroyoshi. Nagasaki bōeki to Kan’ei sakoku [長崎貿易と寛永鎖国]. Tokyo: Tōkyōdō Shuppan, 2003.

Matsukata, Fuyuko, and Joshua Batts. ‘Get It in Writing (If You Can): Regulating Foreign Communities in Tokugawa Japan’. Journal of World History 35, no. 4 (2024): 513–45.

Peng, Hao. Trade Relations between Qing China and Tokugawa Japan: 1685–1859. Springer Singapore, 2019.