The VOC Factories of Bengal

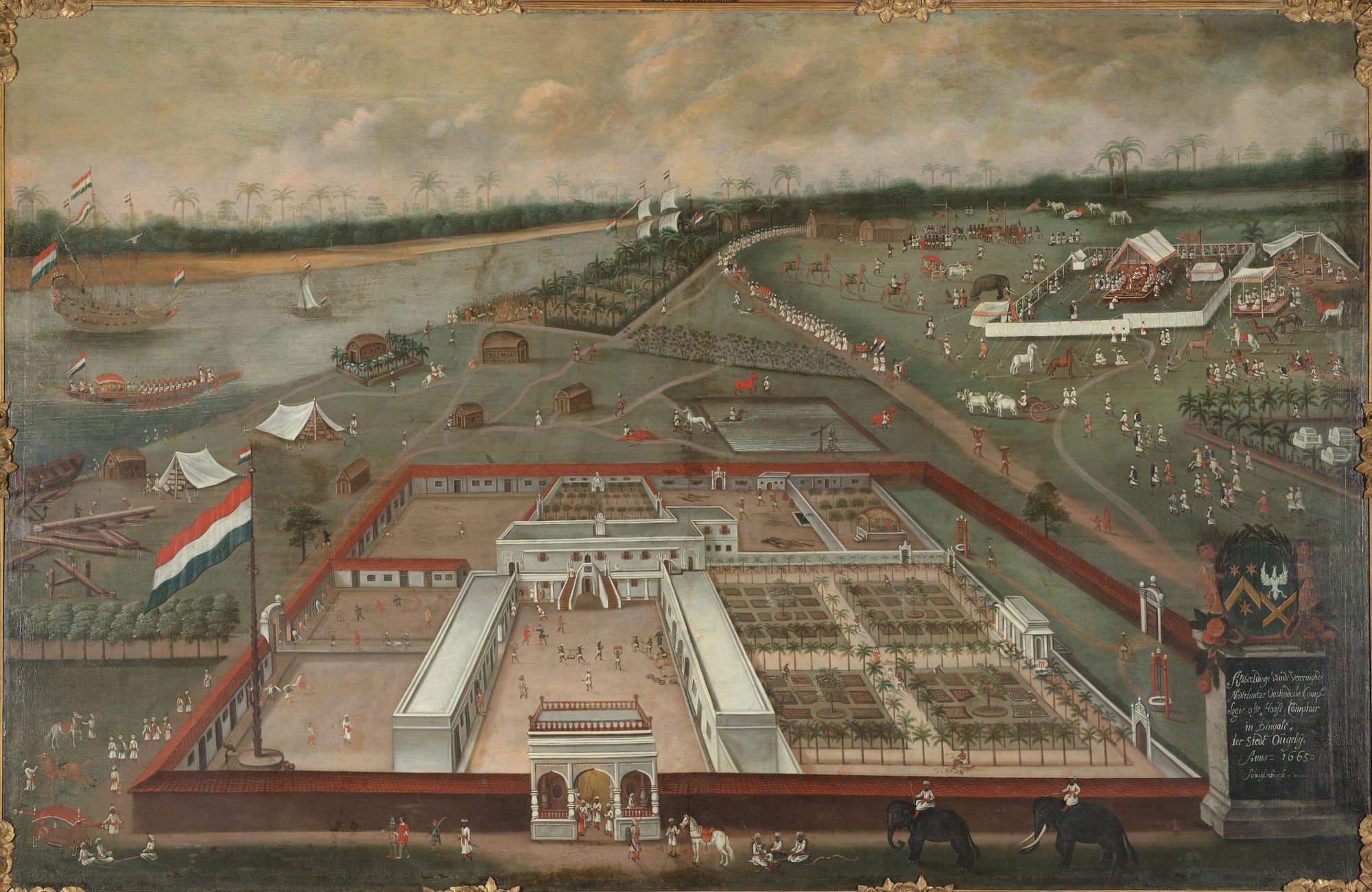

In 1664 a Dutch surgeon named Wouter Schouten spotted the VOC factory in Chinsurah as his ship approached the harbour of Hooghly. Seeing it from a distance, he exclaimed that “nothing shone brighter in Hooghly than the Dutch lodge there, standing tall on a distinct plain, at a musket shot’s range from the waters of the Ganges” (Schouten, Book III: 68). He remarked on how the factory resembled a firm castle that was built out of stones. Its ornate walls and pointed corners were of the right height and equipped with cannons.

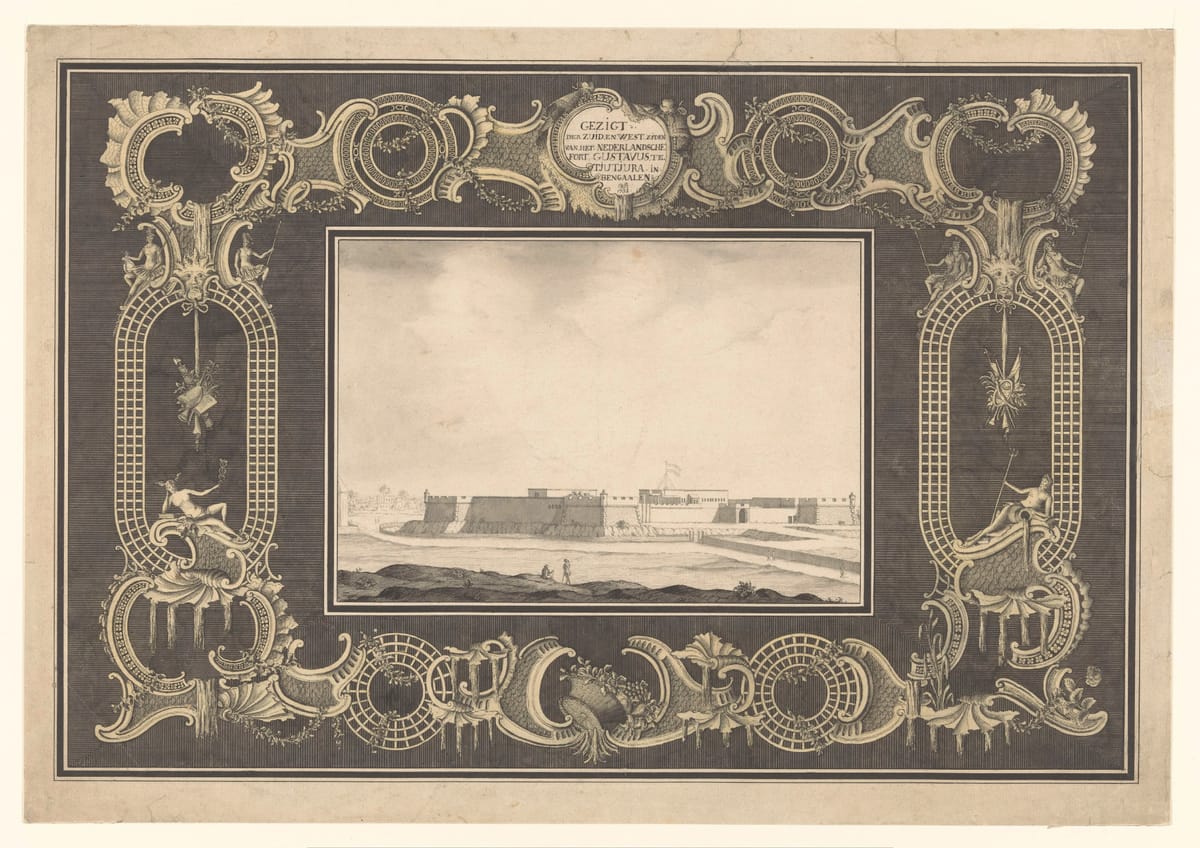

The factory was spacious from inside and had a beautiful lodge for the Dutch director, along with other rooms for the council members and officials of the Company. There was also a warehouse for storing the merchandise that came in and went out daily. This factory with its typical functions of storage and commerce along with residence backed by military support was the primary base for the VOC in Bengal. There were also other factories in Kasimbazaar, Malda, Balasore, Pipli, Patna and Chopra around this region. In 1758, however, the VOC doubted the strength of this factory in Chinsurah to withstand attacks. An engineer employed to design an alternate factory proposed Bankibazaar (modern day Bankipur), close to Hooghly, as the chosen space. Bankibazaar was by then already a much-coveted place. Three decades earlier the Ostend Company had succeeded in establishing a short-lived factory that was closed down by 1731. Subsequently, both the Danish and the English East India Companies wanted to set up their factories. But the plans of the Company never came to fruition and the fortified factory of Hooghly, known as Fort Gustavus continued to be in use. A typical VOC factory, including Fort Gustavus in Chinsurah, had gardens, cemeteries, tanks, storehouses and a lodge for residence and formed micro-settlements within the larger village setting. But what exactly happened inside the factories? Who visited them and how did the men inside interact with those outside?

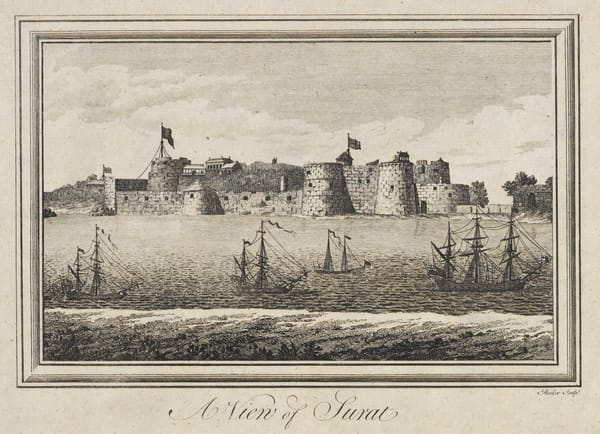

The VOC arrived in the area around the Bay of Bengal in 1602 and set up several trading posts along the Coromandel Coast in India. With its chief Bengal factory first established in 1635 in Hooghly, the company continued in the region to operate until its dissolution in 1800 and after as part of the Netherlands Ministry of Colonies, until 1825. Even though the VOC started out at almost the same time as the English, it eventually lost control of its possessions in Bengal after the British Raj took over. The beginnings of this venture can be traced back to the village of Chinsurah around the port of Hooghly.

When the VOC ships arrived there, the men on board visited the Dutch factory and the lodge and stayed in and around the area adjacent to the factory. To serve their needs better, hostels or inns were started by the Europeans. Several of them were run by the early Portuguese settlers in Bengal. The merchants of the Estado da India in Bengal were used to staying in such hostels that helped them with information on navigating the local surrounding, besides food and lodging. Such hostels continued to operate at the time of the Dutch and other European companies. The VOC surgeon, Schouten, of whom we mentioned before, stayed at such an inn when he arrived in Bengal. He wrote about the owner there as a man speaking creole Portuguese, born of a Roman Catholic father and an Indian mother who hosted him and entertained him in the evenings. Schouten owned a slave and went around the place, often enjoying the hospitality of local merchants as their guests. The area close to the river outside the Dutch factory was thus a bustling scene of people coming from and going to the port as they also mingled with the local populace.

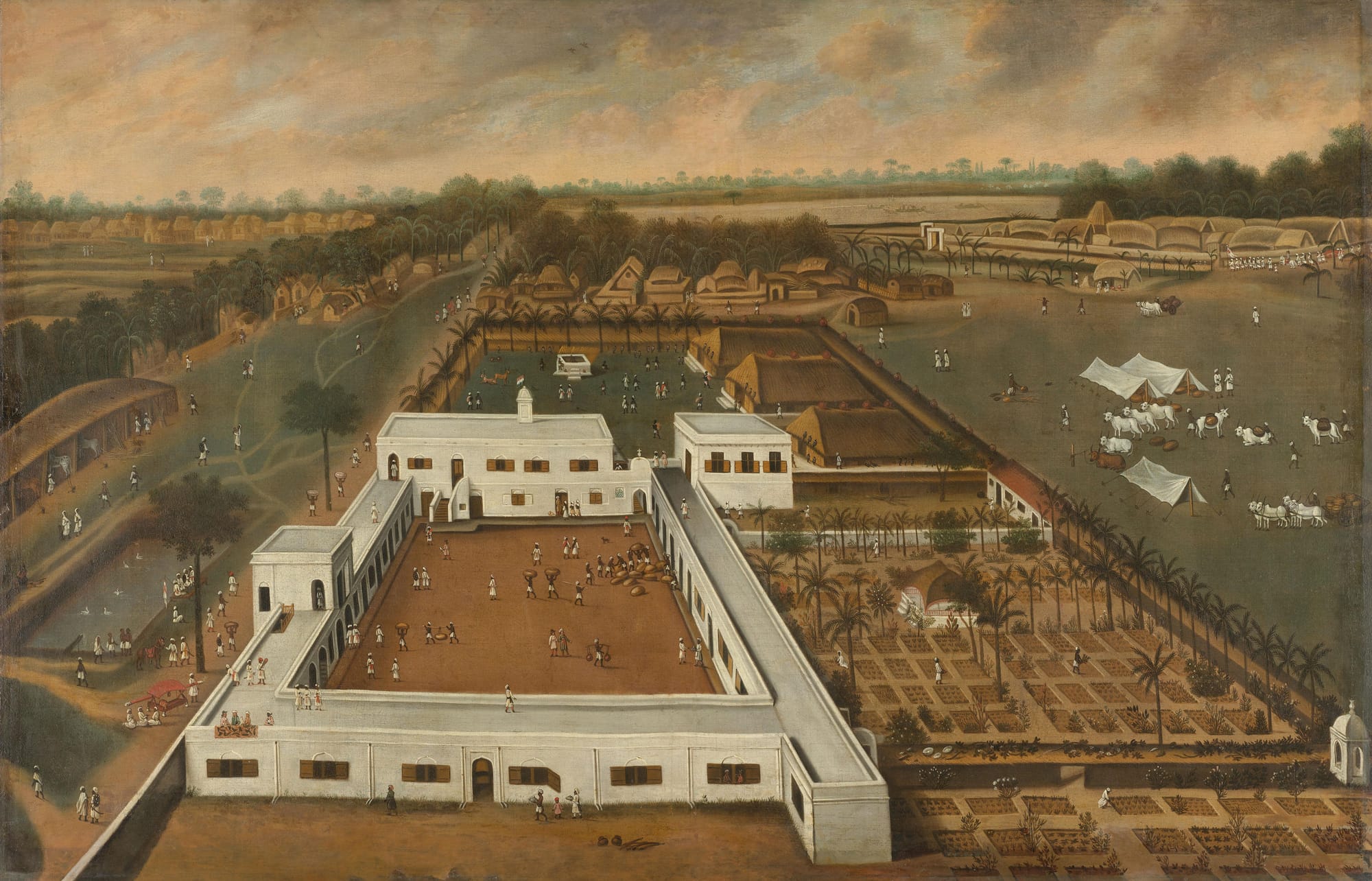

The VOC was accustomed to bargaining for space where it could construct its factories. In the case of Bankibazaar, it was suggested to buy all the houses in the surrounding area. A painting of the VOC factory in Kasimbazaar (below) by Hendrik van Schuylenburgh shows the presence of these local houses in the immediate vicinity of the factory. Here there lived a motley mix of people including Portuguese, Dutch, English, French, Danish and Swedish. By 1824, as per the report of the Dutch resident, Daniel Overbeek, the population of Hooghly was roughly 30,000 people of whom two-thirds lived in Chinsurah, and comprised Hindus, Muslims, Portuguese, Armenians and European Christians. But Overbeek regretted that neither Chinsurah nor Balasore had managed to preserve any of their former glory, and it was Calcutta then that seemed to attract all the crowds.

This was not so in the eighteenth century. The area outside the factory then remained filled usually with people on whom the VOC was dependant for their work. All goods that were brought by the ships anchored in Hooghly were carried in small vessels (called barcquen en chaloupen) to the factory in Chinsurah by the coolies. This spurred great boat-building activities in the surrounding areas of the factory. As can be seen in the painting of the VOC factory at Hooghly by Hendrik van Schuylenburgh (below), there are wooden planks and logs piled on the riverbank, outside the factory wall, which were possibly meant for building boats. Such boat-building activities were also undertaken by some men who came from Surat and settled in Bengal, as Louis Taillefert, the Dutch director of Bengal mentioned in one of his letters to his successor in 1755. Their leader was a merchant named Mulla Mahmed Ali, who fell out with the Mughals and was imprisoned. He later cut himself off from society and lived in isolation with his family on the side of the Ganges where the VOC factory was situated. Here, he built boats and small ships. Most of these local men from outside who could enter the inner quarters of the factory worked as coolies, porters and other labourers for the Company and are seen in the area around the factory in the painting below.

Most of the VOC factories in Bengal were hubs of procurement and storage. The Chinsurah factory eventually became fortified in the style of the Portuguese factory cum fortress. Within it the director lived separately in a lodge. The factory in Chinsurah was governed by a neat hierarchy of officials comprising a council under the director who reported to the Governor-General in Batavia and the directors in Amsterdam. It had a warehouse which stored all the commodities for shipping abroad or across the Indian Ocean. The factory in Chinsurah with its open dalan (courtyard) invited merchants and brokers who negotiated over the prices of procured goods before supplying them to the Company officials. This was primarily true for textiles, including silk from Bengal. The factory in Kasimbazaar was unique in the sense that it was also a site for production. Within its walls, mills were constructed where silk was woven. Such silk was not just traded by the company but also by its officials in their private trade. The Dutch director of Bengal, Jan Albert Sichterman, became a nabob in the middle of the eighteenth century as he amassed huge riches through his private ventures and manufactured silk handkerchiefs (rumals) for trade.

The plan of Fort Gustavus shows the different compartments inside the factory beside the main area. There were gardens, water tanks, a hospital, a church, a cemetery, storage houses for arms and artillery, and a quarter for carpentry. Of the many people who worked inside the factory, one could find gardeners, barbers, washer men, market-goers, coolies, horse attenders, grass mowers, cooks, carpenters, rowers, smiths, guards, artillery men and translators, accountants and scribes. With time, the factories of Bengal were not just limited to commerce but also assumed political functions. Scribes trained in Persian and Bengali languages were appointed to draft documents related to local land administration as the VOC became zamindars of the three villages of Chinsurah, Baranagar and Bazaar Mirzapur. The factory also housed the zamindar’s kacheri or office for paperwork related to civil jurisdiction.

While it is true that factories associated with joint stock corporations like the VOC were spread across different places in Asia and Africa, they also appropriated different forms and types (https://www.capasia.eu/what-is-a-factory/). Most of them were meant for storage and commerce, but a few, like the one in Kasimbazaar in Bengal, took to production. It is worth noting that in Mughal India too, the idea of production in a factory-like-setting was not entirely unfamiliar. There were manufacturing units called karkhanas. Indeed, the Bengali word for a factory to this day is karkhana, originating from its Persian roots. In Ain-i Akbari, Abul Fazl wrote about the presence of different karkhanas of which the ones in textiles were clearly demarcated. There were skilled artisans and weavers from the local areas and from across the subcontinent who made clothes for the royalty with complete knowledge of fabrics from Persia, Europe and China. The Mughals resorted to making them in the karkhanas at a reduced price instead of buying from outside and most of these cloths were meant for internal consumption and not for the market. It is highly likely therefore that weavers who worked in the mills of the VOC in Kasimbazaar were aware of the experience of working in karkhanas or knew of the concept of production in a factory. It opens up questions of whether such existing practices of Mughal manufacturing spaces influenced the VOC to take up production of textiles in their factories and merits further research in the future.

Sources

Abul Fazl, Ain-i Akbari, trans. Francis Gladwin, Vol I (London, 1800). https://archive.org/details/in.gov.ignca.14111/page/n29/mode/2up

Alicia Schrikker and Byapti Sur, “An Empire in Disguise: The Appropriation of Pre-Existing Modes of Governance in Dutch South Asia, 1650-1800”, Law and History Review, Vol. 41, No. 3, (March 2023), pp. 1-25.

Byapti Sur, “The Dutch East India Company through the Local Lens: Exploring the Dynamics of Indo-Dutch Relations in Seventeenth Century Bengal”, Indian Historical Review, Vol 44, No. 1, (June 2017), pp. 62-91.

Jos Gommans, The Unseen World: The Netherlands and India from 1550 (Rijksmuseum: Uitgeverij VanTilt, 2018).

Tirthankar Roy, ‘The Guild in Modern South Asia’, International Review of Social History, Vol. 53, no. S16 (December 2008), pp. 95-120.

Wouter Schouten, Wouter Schoutens oost-indische voyagie (Amsterdam: Jacob Meurs and Johannes van Somere, 1676).

https://archive.org/details/oostindischevoya00scho/page/68/mode/2up