Visualizing Ports for Imperial Oversight: A Case Study of 粵海關志 (the Gazetteer of the Canton Maritime Customs)

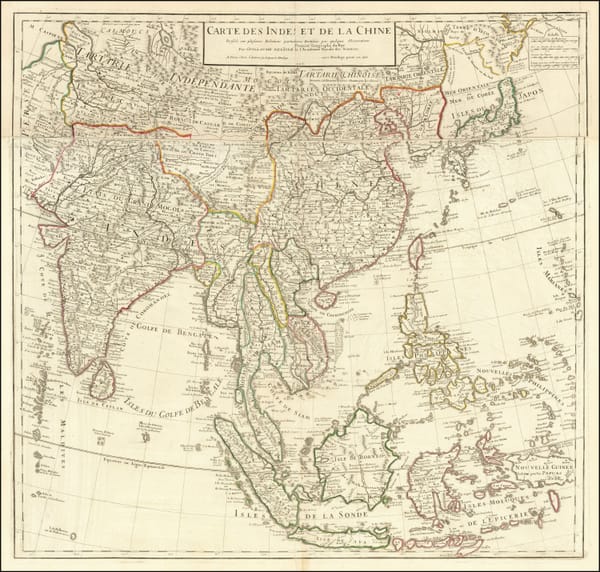

On a fine day in eighteenth-century Canton (modern-day Guangzhou), local residents strolling along the bustling waterfront could see the impressive silhouettes of European cargo ships anchored along the Pearl River. With their towering masts and billowing sails, these vessels marked the seasonal arrival of merchants from more than seven European countries (and colonial America), ready to trade in tea, porcelain, silk, and other commodities highly prized in their home markets. Such sights became more common after the Qing court lifted the maritime ban in 1684 following the subjugation of Taiwan, and officially opened coastal ports in four provinces, including Fujian, Guangdong, Zhejiang, and Jiangsu, to foreign trade. However, this trade network operating through multiple ports was significantly curtailed after 1757, when the Qianlong emperor (r. 1735–1796) restricted all maritime commerce with Europe to Canton (Guangzhou) in Guangdong alone, instituting what became known as the Canton System (yikou tongshang 一口通商). Consequently, Canton became the sole gateway for European traders to access Chinese markets directly, hosting unprecedented levels of commercial activity and cultural exchange within its confines. Situated near Canton and serving as a Portuguese enclave since the 16th century, Macau also played a crucial complementary role in the trade system, functioning as a temporary residence for Europeans during the off-season. This system remained in effect until the Qing government was compelled to reopen additional treaty ports following the Treaty of Nanjing in 1842, ending Canton’s long-standing monopoly on international trade.

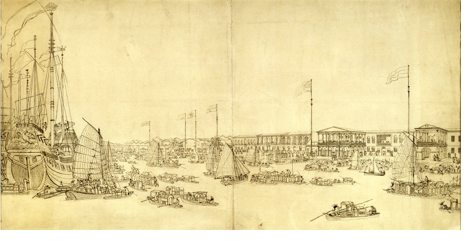

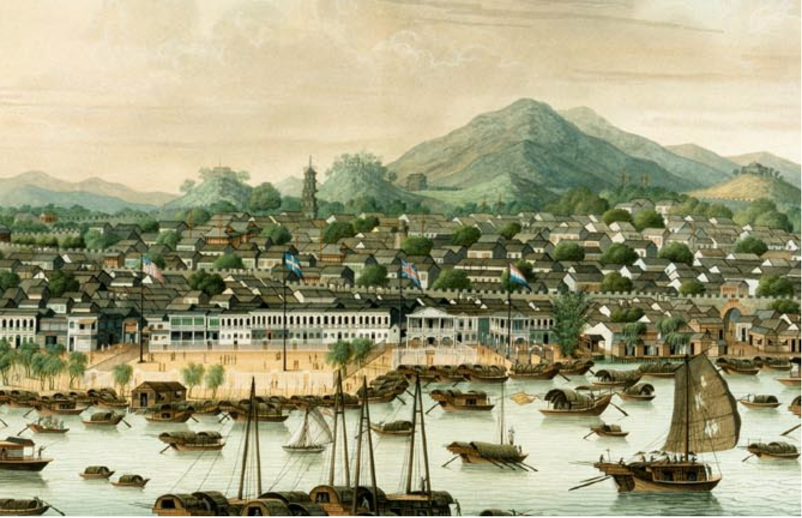

The arrival of European and American merchants transformed Canton’s riverfront into a vibrant trading hub. These foreign traders were confined to a designated commercial quarter along the Pearl River known as the Thirteen Factories/Hongs (十三行), a walled compound where each country maintained its own warehouse, or “factory” (商馆, hong) under strict Qing regulation. Each factory was marked by a distinctive national flag, which turned the shoreline into a display of global commercial rivalries. This international panorama was vividly captured in many contemporary paintings. For example, the 1785 etching Canton Factory Site by British artist William Daniell (1769–1837) was produced during his stop in Canton en route to India (Figure 1). This image shows the sequence of national flags—including, from right to left, Dutch, British, Swedish, Imperial (Austrian), French, and Danish—fluttering atop their respective factory buildings, receding diagonally into the distance along the riverbank. In the foreground, giant cargo ships and smaller boats navigate the busy Pearl River. Soon, local Canton-based painters, such as Guan Lianchang (also known as Tinqua, active 1830s–1870s) and his studio, began producing similar panoramic port views, meeting European consumers’ growing appetite for export paintings depicting this thriving commercial entrepôt. In works produced after 1788 and 1800, respectively, Spanish (Luzon) and American flags also appear.

The very sites that artists turned into icons of global exchange were, for the imperial court, potential flashpoints of illegal private trade and cross-cultural conflict, prompting ever more detailed administrative surveillance. The Qing court’s vigilance toward the international activities of port cities and its desire to centralize control over maritime commerce together contributed to the 1757 decision to close other northern coastal ports. Meanwhile, the resulting monopolization of foreign trade at Canton created the need for new forms of bureaucratic knowledge. Officials in Guangdong produced extensive compilations that documented the city’s maritime infrastructure, customs procedures, financial regulations, and foreign presence.

This brief essay focuses on one important work, Yue haiguan zhi 粵海關志 (Gazetteer of the Canton Maritime Customs), compiled in the early nineteenth century by Liang Tingnan 梁廷枏 (1796–1861). In contrast to the panoramic port views painted for foreign consumption, this gazetteer includes two chapters with illustrations of Cantonese ports that visualize harbors, fortifications, and shipping routes through the lens of strategic concern. A Guangdong official and prolific writer on maritime military affairs, Liang served in various provincial posts, such as the magistrate of Chenghai County and the inspector of Guangdong’s coastal defense. The gazetteer was clearly intended for the emperor as its principal reader, as evidenced by the formulaic opening of each chapter with the phrase chen jin’an 臣謹案 (Your humble minister respectfully records). Thus, its detailed accounts of ports, tariffs, and foreign trade were prepared to match what an emperor would deem politically and strategically useful. Besides Yue haiguan zhi, Liang also authored Haiguo si shuo 海國四說 (Four Treatises on Maritime Countries, 1844), a historical-geographical compendium comprising four treatises: Yesu jiao nan ru Zhongguo shuo 耶穌教難入中國說 (On the Difficulties of Christianity’s Entry into China), Hesheng guo shuo 合省國說 (On the United States of America), Lanlun ou shuo 蘭倫偶說 (Miscellaneous Discourses on England), and Yuedao gongguo shuo 粵道貢國說 (On the Tribute Missions from Guangdong to Foreign States). These works systematically surveyed the histories, geographies, and political systems of various Western nations, providing strategic knowledge of the maritime world in light of growing Western encroachment.

Today, a Daoguang-period printed edition of Yue haiguan zhi is preserved in Cornell University Library’s Rare Book Collection, published in Guangzhou by Yingwen Tang 應文堂 during the 1840s. This volume is one of the earliest extant impressions of the work. In the introduction, Liang states that he compiled the gazetteer in order to “clarify laws and maintain proper standards (以昭法守).” Unlike the Ming, which restricted legal trade to tribute ships alone, the Qing maintained the tribute framework but also permitted merchant vessels to trade under taxation:

[During the Ming,] Tribute ships were recognized by royal law; they were permitted to conduct trade publicly through the shibo (maritime trade offices). Merchant ships, not permitted by royal law, were not supervised by the shibo and thus engaged in private trade. Under the Ming system, markets existed only because of tribute; those who did not enter with tribute were not allowed to engage in trade…Our dynasty (the Qing), by contrast, acts with broad impartiality: those who come accompanying tribute should be exempt from taxes, while those who come solely for commerce should have their goods taxed accordingly. This is why the various overseas peoples both fear and respect us.

The gazetteer is organized into thirty juan (volume/chapter), arranged under fourteen thematic categories:

· 1 chapter of huangchao xundian 皇朝訓典 (Imperial Edicts and Instructions), which compiles Qing court edicts from the first year of the Shunzhi reign (1644) to the third year of the Daoguang reign (1823).

· 3 chapters of qiandai shishi 前代事實 (Historical Precedents), which compile accounts from earlier periods, providing historical context for Canton’s maritime customs administration.

· 2 chapters of kou’an 口岸 (Ports), which describe the distribution and orientation of all ports under the jurisdiction, accompanied by illustrations.

· 1 chapter of sheguan 設官 (Official Appointments), which outlines the evolution of customs official systems from the Tang through the Qing.

· 6 chapters of shuize 稅則 (Tariffs), which lay out tax regulations, duties, and schedules.

· 2 chapters of zouke 奏課 (Reports and Assessments), describing the internal management system of the Canton Maritime Customs, including performance evaluations and reporting procedures.

· 1 chapter of jingfei 經費 (Finances), including the fiscal expenditures of the Customs.

· 3 chapters of jinling 禁令 (Prohibitions), listing bans, restrictions, and enforcement measures.

· 1 chapter of bingwei 兵衛 (Military Defense), which records the defensive arrangements along the route from the inner seas to Huangpu.

· 3 chapters of gongbo 貢舶 (Tributary Ships), which are presented through the framework of the traditional tributary system. Over twenty countries are listed in this section, such as Siam, Ryukyu, the Netherlands, England, and Italy, whose vessels were exempt from customs duties.

· 1 chapter of shibo 市舶 (Trading Ships), which includes purely commercial vessels (as opposed to tributary ones) subject to taxation, including those from the United States, Japan, Russia, Vietnam, Luzon, and other Southeast Asian and European states.

· 1 chapter of hangshang 行商 (Licensed Merchants), recording the system of officially licensed Chinese merchants, more famously known as the “Thirteen Hongs.”

· 4 chapters of yishang 夷商 (Foreign Merchants), which provide detailed accounts of Qing policies toward foreign traders in Guangzhou before the Opium War.

· 1 chapter of zashi 雜識 (Miscellaneous Records), which collects various anecdotes and unusual accounts related to overseas trade.

For each category, Liang collated earlier historical records and supplemented them with detailed, up-to-date Qing reports from local officials. For instance, the Netherlands, classified as one of the “Tributary Ships,” is first introduced in terms of its diplomatic history and military conflicts with China since the Ming dynasty (1368–1644). Qing dynasty regulations governing Dutch tribute and trade follow, detailing the frequency, scale, and other logistical requirements to be observed by both Dutch envoys and Qing officials attending to the matter. The entry concludes with a record of all Dutch tributary missions to China during the Qing period up to Liang’s own time.

Importantly, only chapters 5 and 6 on kou’an 口岸 (Ports) are dominated by illustrations. A brief introduction at the beginning of these chapters sets the scope and rationale. In surveying the maritime frontiers from east to west and north to south, Liang carefully distinguishes the establishment of customs ports from coastal defense in terms of administrative priorities: “coastal defense emphasizes difficult terrain that is hard to penetrate, while customs ports are situated for accessibility and ease of passage.” He then classified and listed the ports established by the Guangdong Maritime Customs into three types based on their functions: 31 principal tax-collection ports (zhengshui zhikou 正税之口), 22 inspection ports (jicha zhikou 稽查之口), and 22 registration ports (guahao zhikou 掛號之口). Crucially, the final section of the text justifies the use of illustrations. As Liang observed, with ships constantly docking along Guangdong’s coastline, routes and harbors were too numerous to grasp through description alone. Therefore, “control cannot be exercised without recourse to maps.”

The two chapters include a total of 51 illustrated maps of different institutional sites, ranging from administrative offices and military forts to riverine checkpoints and maritime ports. They cover the entire Guangdong coastline, from Chaozhou 潮州 in the east to Lianzhou 廉州 (modern Beihai) in the west, as well as key riverine checkpoints along the Pearl River Delta, such as Humen 虎門, and major harbors on Hainan Island (e.g. Haikou 海口). Liang’s decision to provide extensive maps draws on a long-standing tradition in which maps (yutu 輿圖) carried both strategic and symbolic significance for the court. Maps spoke directly to their audience’s spatial intuition, clarifying directions, distances, and boundaries in ways that textual description could not. At the same time, mapmaking was never a purely objective endeavor. The symbols, labels, and graphic conventions employed in these port maps conveyed an interpretive perspective shaped by contemporary administrative priorities and spatial imaginaries.

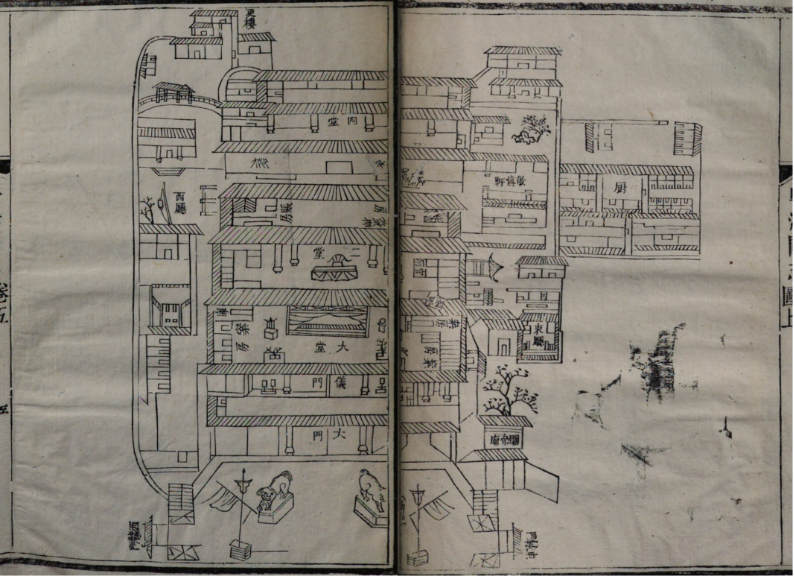

The main section opens with the illustration and introduction of Daguan 大關, the principal customs office (Figure 2). According to the accompanying text, Daguan was established in Canton in the 24th year of the Kangxi reign (1685), a year after the Qing court formally reinstated maritime trade. Situated just inside Wuxian Gate (五仙門), one of the southern gates of the city, it served as the administrative headquarters of the Imperial Maritime Customs, with facilities such as silver vaults and warehouses. The illustration is presented not as a topographical map but as an architectural plan of the compound, with courtyards, halls, gates, storerooms, offices, and other structures laid out. Most of the ports discussed in the two chapters are described in relation to their geographical distance from Daguan, underscoring its administrative importance.

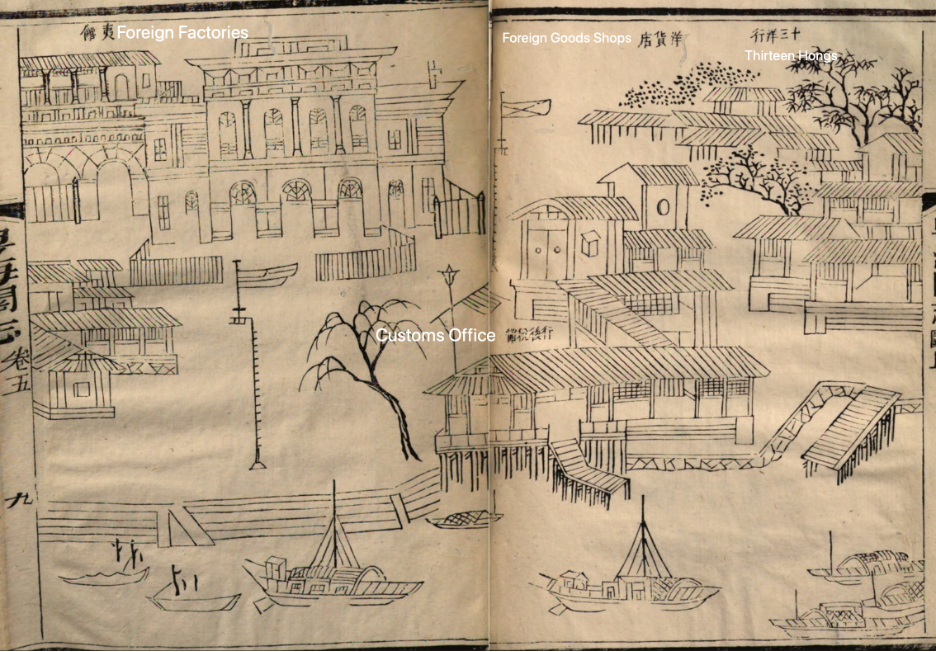

Located just outside the southern city wall of Canton, the famous Thirteen Hongs stand along the Pearl River. This district appears in the illustration of Hanghou Port 行後口, or the Merchant Guild’s Rear Port (Figure 3). The Hanghou Port is classified as an inspection port, located in Nanhai County adjoining Canton city, and placed under the jurisdiction of the Chief Inspection Port 總巡口. The illustration follows the Chinese pictorial convention of assuming multiple perspectives. Boats and wharves in the foreground establish the scene on the Pearl River, rendered as if from a slightly elevated, bird’s-eye vantage point. From there, a corridor-like structure extends inland toward the customs office 行後稅館, depicted frontally at eye level. This contrasts with the adjacent clusters of buildings, which are rendered obliquely from the right. At the very back of the right half of the image, more schematically drawn structures interspersed with vegetation are labeled “Thirteen Hongs” 十三洋行 and “foreign goods shops” 洋貨店. Yet, the actual factory compound is more plausibly represented on the left, where several monumental Western-style buildings are marked as the Foreign Factories 夷館. These factories dominate much of the background and, like their counterparts in export paintings, are distinguished by arched gates, tall pillars, rows of windows, and enclosing fences that demarcate the compound from the surrounding city.

Although the illustration in Yue haiguan zhi appears schematic at first glance, comparison with an export painting from around 1800 (Figure 4) helps to anchor its location at the eastern periphery of the Thirteen Hongs: the characteristic façade of the French factory—with its rows of arched windows—is readily identifiable. To its left, the recessed structure adjoining the British factory is also carefully noted. The riverscape in the foreground, densely populated with boats, further echoes the compositional strategies of many export paintings. Such visual parallels suggest that the gazetteer illustration likely borrowed from the contemporary pictorial idioms used in paintings to depict the foreign factories. In this sense, this illustration participated in a shared visual repertoire that had already become conventionalized for representing the Thirteen Hongs, translating their recognizable features into the gazetteer’s bureaucratic format.

In the meantime, the illustration foregrounds the customs office by placing it prominently at the center—a pictorial feature absent from export paintings. Customs offices were established at virtually all ports to register goods and collect tariffs. The Hanghou Port, however, is described in chapter 9 on “Tariffs” as a subsidiary checkpoint that did not collect silver duties. Its personnel were dispatched only to inspect foreign ships upon entry and were withdrawn once the vessels completed their departure procedures. In fact, only tax-collection ports were authorized to levy duties, a policy intended to curb corruption at smaller stations.

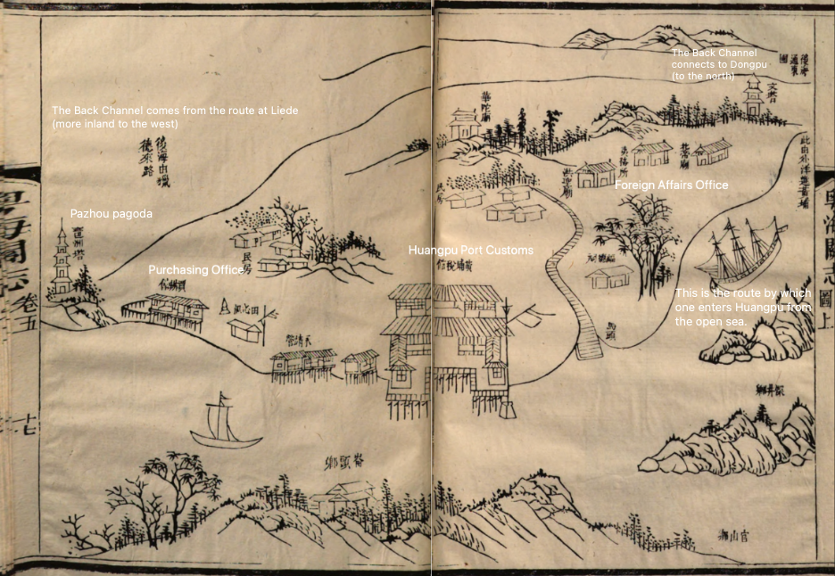

In other illustrations of ports within these two chapters, such as that of the Huangpu (Whampoa) Port 黃埔口圖 (Figure 5), the customs office also features prominently in the center, labelled as the Huangpu Port Customs 黃埔稅館. The repeated centering of customs offices in these port illustrations underscores that regulation and taxation were the primary concerns from Liang’s perspective. This port, located about thirty li downstream on the Pearl River from Daguan, functioned as a registration port, where Liang recorded that many foreign vessels carrying rice docked. At the same time, Huangpu was also a notorious hub of the illicit opium trade: despite successive prohibitions between 1809 and 1817, smuggling thrived through collusion between local officials and merchants, and opium was even openly exchanged at both Macau and Huangpu itself.

Unlike the other examples discussed, this illustration adopts a composite bird’s-eye view, directing the viewer to look obliquely from the top right at Huangpu’s layout and its integrated water-gateway system. The government established two key institutions in Huangpu: a Foreign Affairs Office (夷務所), which managed interactions and regulations concerning foreign ships and crews, and a Purchase Office (買辦館), which facilitated communication and transactions between foreign traders and local officials. Both are present in the illustration. Using a contemporary digital cartographic map as a reference (Google Maps, Figure 6), the Back Channel, now marked as “Qian Hangdao,” connects westward to Liede Village 獵德 and northward to Dongpu 東圃 District; the front waterway represents the route by which “one enters Huangpu from the open sea.” By clearly delineating these waterways and their directions, the illustration effectively situates Huangpu within a larger fluvial network, thus demonstrating the logistical routes by which foreign ships were admitted and registered.

A well-regulated customs port cast in Liang’s gazetteer, Huangpu was transformed during the First Opium War into one of the key frontlines, when in early 1841 British warships forced their way past the Bogue defenses and pushed directly into its anchorage. Yet this very rupture barely surfaces in Liang’s own writings. Yue haiguan zhi, finished before the first tremors of the Opium War (1839–1842), stands as one of Liang’s early works. Surprisingly, his later compilations, such as Haiguo sishuo, still did not register Qing’s traumatic defeat. Instead, Liang continued to recycle older genres and materials: tributary records, port gazetteers, geographical notes, and anecdotal accounts of foreign lands. Written in 1844, in the immediate aftermath of the war, Liang’s silence about this moment of rupture raises a larger question: should we read it as a matter of caution, a reluctance to acknowledge imperial weakness too openly, or as an intellectual discipline that sought to absorb even defeat into established bureaucratic routines? This “silence” strategy did not ultimately succeed in containing the reality of foreign aggression, but its very persistence is significant: it suggests that Liang’s project was more about containing changes than ignoring them. Like many of his contemporaries, he recast the destabilizing encounter with foreign power into the familiar frameworks of port management and tribute in order to maintain the appearance of order in a world unsettled.

References:

Primary Source:

YHGZ. Liang, Tingnan 梁廷枏. Yue haiguan zhi 粵海關志. Guangzhou: Yingwen Tang 應文堂, Daoguang period [1840-]. HathiTrust Digital Library, https://catalog.hathitrust.org/Record/100580420.

Secondary Source:

Chen, Enwei 陳恩維. “Liang Tingnan Yue haiguan zhi ji qi haiguan shi yanjiu 梁廷枏《粵海關志》及其海關史研究.” Shixue shi yanjiu 史學史研究 135, no. 3 (2009): 72–80.

Ding, Ning 丁宁, and Zhou Zhengshan 周正山. “Liang Tingnan yu Yue haiguan zhi 梁廷枬与《粤海关志》.” Xueshu yuekan 学术月刊 18, no. 6 (1986): 74.

Guo, Tingyi 郭廷以. Jindai Zhongguo shigang 近代中國史綱. Hong Kong: Xianggang Zhongwen daxue chubanshe, 1979.

Perdue, Peter C. “The Rise and Fall of the Canton Trade System III: Canton & Hong Kong.” Visualizing Cultures. Massachusetts Institute of Technology, 2009. https://visualizingcultures.mit.edu.

Ptak, Roderich. “Macau: Trade and Society, circa 1740–1760.” In Maritime China in Transition, 1750–1850, edited by Wang Gungwu and Ng Chin-keong, 191–211. Wiesbaden: Harrassowitz Verlag, 2004.

Van Dyke, Paul A. The Canton Trade: Life and Enterprise on the China Coast, 1700–1845. Vol. 1. Hong Kong: Hong Kong University Press, 2005.

Van Dyke, Paul A., and Maria Kar-wing Mok. Images of the Canton Factories, 1760–1822: Reading History in Art. Hong Kong: Hong Kong University Press, 2015.

Zhao, Gang. The Qing Opening to the Ocean: Chinese Maritime Policies, 1684–1757. Honolulu: University of Hawai‘i Press, 2013.